Landscape painting by Italian artist Marco Ricci (1676-1730)

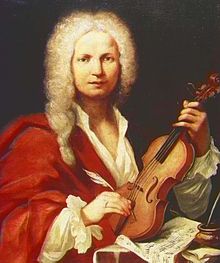

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Vivaldi was an Italian celebrity of the Baroque period. He wrote more music in his lifetime than just about anyone else on the planet — 50 operas, 40 pieces for choir and orchestra, 100 works for orchestra alone, 500 concertos for solo instruments with orchestra.

When he came of age, he decided to become a priest. With his crop of curly red hair (don’t be fooled by the white wig), he was nicknamed The Red Priest. He didn’t last very long as a priest, though. One day during mass, a great tune popped into his head. Without hesitation or apology, he stepped down from the altar and dashed into the next room to get the tune on paper. He was brought before a tribunal which decreed that he could never say the Mass again.

The fate of the Italian composer’s legacy is unique. After the Napoleonic wars, it was thought that a large part of Vivaldi’s work had been irrevocably lost. However, in the autumn of 1926, after a detective-like search by researchers, 14 folios of Vivaldi’s previously unknown religious and secular works were found in the library of a monastery in Piedmont, Italy. To its amazement, the world of music was presented with 300 concertos for various instruments and 18 operas, not counting a number of arias and more than 100 vocal-instrumental pieces.

Concerto For Two Trumpets (early 1700s)

In this gloriously bright work for two trumpets and string orchestra, Vivaldi displays the Venetian love of musical dialogue. It was one of the few solo works of the early 1700s to feature brass instruments.

“The Harmonic Inspiration” is a set of 12 concertos for stringed instruments. It was the first publication to fully reveal Vivaldi’s inventive genius and one which established the fast-slow-fast movement formula present in the greater part of his concerto output. Vivaldi scholar Michael Talbot described the set as, “perhaps the most influential collection of instrumental music to appear during the whole of the eighteenth century.”

Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons (1720-1723)

Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons (1720-1723)

Inspired by landscape paintings by Italian artist Marco Ricci, Vivaldi composed the Four Seasons roughly between 1720 and 1723, and published them in Amsterdam in 1725. The Four Seasons consists of four concerti (Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter), each one in a distinct form containing three movements with tempos in the following order: fast-slow-fast.

Since its publication, musicologists consider Vivaldi’s Four Seasons to be among the boldest program music ever written during the Baroque period. When composers write a musical narrative set to a line of text, a poem, or any other form of writing (which is typically published within the concert’s program notes), that is said to be program music. Program music wasn’t a technique that was typically employed during the Baroque period (in fact, the term “program music” wasn’t invented until the romantic period), so Vivaldi’s work is quite unique.

SPRING starts with the clarity and crispness of a typical spring day, accompanied by the choirs of birds and streams. It is invaded by a sudden thunderstorm, but the singing birds soon regain dominance. The movement ends with a lively country dance, with inhabitants celebrating the return of fauna and flora after a harsh winter. SUMMER offers a slow start, portraying the weather as too hot for any movement. The air is almost at a standstill, the birds chirping away lazily until a breeze gathers up, whipping the warning of an imminent storm. The most striking moment is served in the third movement, as a hail storm mercilessly rains down, offering a perfect contrast.

SUMMER offers a slow start, portraying the weather as too hot for any movement. The air is almost at a standstill, the birds chirping away lazily until a breeze gathers up, whipping the warning of an imminent storm. The most striking moment is served in the third movement, as a hail storm mercilessly rains down, offering a perfect contrast.

AUTUMN returns to the clarity resembling “Spring,” with similar musical themes in the first movements. The country-folk rejoice once again, celebrating the harvest by drinking wine. The tempo drops significantly, in parallel to the peaceful sleep that engulfs the people. The final movement illustrates a hunt.

WINTER – The opening movement resembles a shivering person, stamping his feet in rhythm to stay warm. The middle movement portrays the pleasure of getting warm inside through a crackling fire. The final movement offers people outdoors walking down icy paths, while people inside houses feel the relentless chill finding its way inside.

Concerto for Lute in D Major, RV 93 (c. 1730s)

This concerto comes from Vivaldi’s globe-trotting period (or at least Europe-trotting period). It was written in Bohemia and never saw publication in his lifetime.

Nulla In Mundo Pax Sincera (1735)

Sublime motet of three arias and interlinking recitatives for solo soprano and string orchestra. It is considered to be one of Vivaldi’s most beautiful solo motets and is famous for its lilting first movement. The title may be translated as “In this world there is no honest peace” or “There is no true peace in this world without bitterness”.

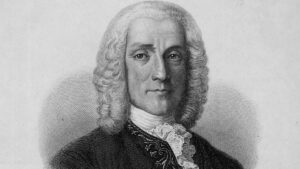

George Philipp Telemann (1681-1767)

Telemann was a self-taught musician and a lifelong friend of Handel. During his lifetime, Telemann was more widely renowned than Bach for his musical abilities.

His father and brother were Lutheran clergymen, and a similar career was intended for Georg. His mother confiscated all his instruments, but when his teachers discovered his talent they encouraged him. He started composing at the age of 10 and wrote music as if there were no tomorrows. However, he had a lot of tomorrows for he lived to be 86.

Telemann’s compositions were prolific, mainly concertos, orchestral suites, and chamber works. Generally they are lighter than the music of his contemporary, J.S. Bach, written in the ‘style galant’ which was fashionable at that time. The ‘galant’ style is characterized by tuneful melodies, lucid textures, and a feeling of relaxed elegance and grace. Much of it was intended for amateur players, and so is not difficult to play.

Sonata in F Major for 2 Chalumeaux

The chalumeaux was an early form of clarinet, but only sounding the lower register. This is why today we call the low register of the modern clarinet the chalumeau register.

Viola Concerto in G Major, TWV 51: Allegro (1716-1721)

Concerto in F minor for Trumpet: Vivace (1728)

Concerto for Mandolin, Hammered Dulcimer and Harp in F Major, TWV 53 (c. 1733)

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764)

A top French composer of the 18th century. Not a natural genius, his music is the result of much hard work and study. He wrote 250 years ago, “Music is dead,” meaning that all feasible combinations had been found and tried.

He once spent six years as a church organist in Provence. When he tired of the job, but the directors would not release him, he reacted by playing as badly as possible one Sunday. It worked. He was kicked out.

He did not achieve prominence until he was about 39, with a book on harmony. Then when he was 50 his operas became well-known. Rameau’s music had gone out of fashion by the end of the 18th century, and it was not until the 20th that serious efforts were made to revive it.

“The Conference of Birds.” Rameau doesn’t quote birds literally, it’s more of a generic use of birdsong to create the effect of birds calling and responding to each other.

Pieces de Clavecin, E Minor Suite: X. Tambourin (1724)

Premier Concert – La Venizet (1760)

Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757)

Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757)

Scarlatti was one of the greatest late-developers in musical history, composing more than 550 sonatas in the last 18 years of his life. The catalyst appears to have been his introduction to the ceremonial, folk and popular music of the Iberian peninsula, where he spent the last quarter of his life; first in Portugal and later at the royal court of Spain.