Romantic Era

(1820-1900)

The previous Age of Reason was too “reasonable” for the Romanticists. They valued heightened emotion over elegance. The resulting music of Schumann, Chopin, Wagner, Tchaikovsky, Verdi and Puccini were some of its greatest accomplishments.

Beethoven and Schubert bridged the gap between the Classical and Romantic periods of music. Just as one might assume from the word “romantic,” this period took Classical music and added overwhelming amounts of intensity and expression. As the period developed, composers gradually let go of heavily structured pieces and gravitated towards drama and emotion.

Instrumentation became even more prominent, with orchestras growing to higher numbers than ever before. Composers experimented in new ways, trying out unique instrumentation combinations and reaching new horizons in harmony. Public concerts and operas moved away from the exclusivity of royalty and riches and into the hands of the urban middle-class society for all to enjoy.

The Romantic period was also the first period where national music schools began to appear. This era produced some of music’s most adored composers, including Hector Berlioz, Frederic Chopin, Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, Johannes Brahms, Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and Richard Wagner. The very end of the Romantic period also included the composers Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Giacomo Puccini, Jean Sibelius, Camille Saint-Saëns, Gabriel Fauré, and Sergei Rachmaninoff.

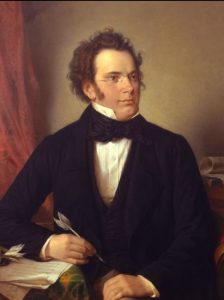

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Schubert’s life seems to follow, tragically, the cliché of the Romantic artist: a suffering composer who languishes in obscurity, his genius only appreciated after his untimely death. While Schubert did enjoy the respect of a close circle of friends, his music was not widely received during his lifetime.

Though I include him in the Romantic era, Schubert does not fit neatly into the Romantic period. Like Beethoven, Schubert is a transitional figure. Some of his music—particularly his earlier instrumental compositions—tends toward a more classical approach. However, the melodic and harmonic innovation in his art songs and later instrumental works sit more firmly in the Romantic tradition.

Schubert lived during the late years of Beethoven, and was able to meet him on two occasions. Once at a concert in Vienna. The second by request of Beethoven as he was on his death bed. Thus showing that Beethoven held Schubert’s talent in high regard, believing him to be the next great Viennese composer. (Schubert served as a pall bearer at Beethoven’s funeral) And Schubert proved to be so. In the history of western classical music, Schubert is considered the first great composer of the Romantic Era.

From the very opening, we hear the voice of a spinning wheel mimicked in the piano part. The high running part in the right hand represents the spinning wheel as it spins; the bass notes Gretchen’s foot on the pedal making the wheel spin. The song is set in rondo form where the original A section is Gretchen’s reality, and the wandering sections in between her remembrance of her love, and her rising emotions. The climatic moment coming when Gretchen sings “his kiss”. The spinning wheel stops as she swoons, and begins again as she returns to reality. As the piece continues, the constant motion of the spinning wheel comes to symbolize Gretchen’s racing emotions, as much as the spinning wheel itself.

My peace is gone, My heart is heavy; I shall never find peace, never again.

When he is not with me, Life is like the grave; The whole world Is turned to gall.

My poor head Is crazed, My poor mind shattered.

My peace is gone, My heart is heavy; I shall never find peace, never again.

Only for him I gaze from the window, Only for him I leave the house.

His proud bearing, his noble form, The smile on his lips, The power of his eyes,

And the magic flow of his words, The touch of his hand, And ah, his kiss!

My peace is gone, My heart is heavy; I shall never find peace, never again.

My bosom yearns for him.

Ah! if I could clasp and hold him, And kiss him to my heart’s content,

And in his kisses perish!

My peace is gone, My heart is heavy;

Piano Quintet in A Major, “Trout” (1819)

Schubert is at his most buoyant and delightful in his ‘Trout’ Quintet, one of his best works. By adding a double bass to the piano quartet he not only underpinned his rhythms with a bounce, but liberated the cello as lyric tenor: no one before or since has matched his achievement with these forces. A spacious opening unfolds into a breezy divertimento, the piano’s silken arpeggios and trills intensifying into the cello’s melody, followed by a serenade that explodes into a scherzo. Then we’re transported to Upper Austria’s “unimaginably beautiful scenery” (Schubert’s own description) for variations on the song melody of Die Forelle (The Trout), which scintillates in sparkling waters.

Piano Sonata in A-Major, D664 (1819)

Schubert composed this sonata when he was on a two-month vacation at a place in Austria called Steyer. It was composed for the daughter, Josephine, of his host there. This is music which depicts the loveliness of Nature in Steyer, and undoubtedly the loveliness of Josephine.

Du bist die Ruh, Op. 59, No. 3, D. 776 (1823)

You are repose and gentle peace.

You are longing and what stills it.

Full of joy and grief I consecrate to you my eyes and my heart as a dwelling place.

Come in to me and softly close the gate behind you.

Drive all other grief from my breast.

Let my heart be full of your joy.

The temple of my eyes is lit by your radiance alone: O, fill it wholly!

Auf dem Wasser zu singen, Op. 72 D. 774 (1823)

Amid the shimmer of the mirroring waves

the rocking boat glides, swan-like,

on gently shimmering waves of joy.

The soul, too, glides like a boat.

For from the sky the setting sun

dances upon the waves around the boat.

Above the tree-tops of the western grove

the red glow beckons kindly to us;

beneath the branches of the eastern grove

the reeds whisper in the red glow.

The soul breathes the joy of heaven,

the peace of the grove, in the reddening glow.

Alas, with dewy wings, time vanishes from me on the rocking waves.

Tomorrow let time again vanish with shimmering

wings, as it did yesterday and today,

until, on higher, more radiant wings,

I myself vanish from the flux of time.

Symphony No.8 In B minor, D759 – ‘Unfinished’ Symphony (1822)

Schubert’s early symphonies are breezy and Classical, barely hinting at the indelible voice of the mature composer. In the ‘Unfinished’, though, it as if he takes up where Beethoven left off in the ‘Pastoral’ Symphony, opening out visionary new vistas that will lead to the great Romantic symphonies. Though only two complete movements remain, they complement each other in some mysterious way, and the perfection of the lyric writing has ensured it a permanent place in the concert repertoire.

John Field (1782-1837)

John Field (1782-1837)

John Field was an Irish pianist, composer, and teacher. He was born in Dublin into a musical family and received his early education there. The Fields soon moved to London. where Field quickly became a famous and sought-after concert pianist.

Field was very highly regarded by his contemporaries, and his playing and compositions influenced many major composers, including Frédéric Chopin, Johannes Brahms, Robert Schumann, and Franz Liszt. He is best known today for originating the piano nocturne, a form later made famous by Chopin, as well as for his substantial contribution, through concerts and teaching, to the development of the Russian piano school.

Nocturne No. 5 in B flat major (1817)

If you liked this piece, here are the rest of Field’s nocturnes – a wonderful background for a peaceful day at home.

Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826)

Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826)

Weber was a conductor, pianist, guitarist, critic, and one of the first significant composers of the Romantic school. He was born in Germany, in 1786, to a very famous, musical family. He was a very weak child, born with a damaged hip that would cause him to limp for his entire life.

Weber learned to play piano while traveling with his father’s theater company. He took lessons from his half-brother, Fridolin, while on the road, and from local teachers wherever the company paused. A restless and charming young man, he traveled all over Europe, studying music with famous teachers (including Joseph Haydn‘s younger brother, Michael) wherever he went.

During Weber’s career, he served as the Music Director of opera houses in Breslau, Prague, and Dresden. He worked hard to improve the quality of opera in each of these cities by employing bigger orchestras, performing more challenging repertoire, and seeking out fresh singers. Weber wanted musicians and audience members to appreciate German opera as much as they appreciated Italian opera, and he wrote many of his own, including Der Freischütz, Euryanthe, and Oberon.

Weber was one of the very first conductors to use a baton (although he held it in the middle instead of at the end, like conductors do today). He loved conducting, and audiences often remarked on how excited he became during performances.

Weber suffered from tuberculosis the last three years of his life, dying on June 5, 1826. He is best remembered for his wonderful, virtuosic compositions for clarinet and for setting the standard for German romantic operas. His music inspired many later composers, such as Wagner, Berlioz, Mahler, Hindemith, and Debussy.

Invitation to the Dance, Op. 65, J. 260 (1819)

The “Invitation to the Dance,” the most brilliant example of dance music yet written, was composed by Weber in 1819, and dedicated to his wife, Caroline.

It is related in the biography of Weber, by his son, that while the composer was playing the piano version of the “Invitation” to his wife, he gave her the following program of the piece: First appearance of the dancers, the lady’s evasive reply, his pressing invitation, her consent, waiting for the commencement of the dance. They dance and then, at conclusion of the dance, his thanks, her reply, and their retirement.

Fresh, graceful, and spirited, the work is the very apotheosis of the dance. It marks the transition to a more modern dance music. The waltz had been previously a sort of mere animated minuet, but Weber threw a fiery allegro into the dance. The world ran faster, why should not people dance faster?

Oberon, the final opera of Weber was premiered at London’s Covent Garden in 1826. The three-act opera, set in English with spoken dialogue, was described as “one of the most remarkable combinations of fantasy and technical skill in modern music.”

Based on a thirteenth century French epic poem by Huon of Bordeaux, it tells the story of Oberon, the Elf King, who has argued with his wife, Titania, regarding who is less faithful in marriage, men or women. Oberon has “vowed not to be reconciled with her until a pair of human lovers are found who have been faithful to each other through all perils and temptations.” With the inclusion of the trickster Puck and the magic of mischievous fairies, there are obvious parallels with Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

The overture begins with a plaintive, mystical horn call, a reference to the “magic horn” which plays a central role in the opera’s story. Ebullient “fairy laughter” dances through the woodwinds. The overture concludes with a virtuosic flourish. With the added power of three trombones, the final chord shows the grandeur of the expanded, nineteenth century orchestra.

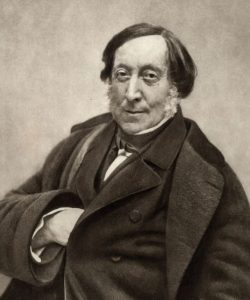

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868)

Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868)

Rossini was an Italian composer. He sang in church and in minor opera roles as a child, began composing at age 12, and at 14 entered Bologna’s conservatory, where he wrote mostly sacred music.

From 1812 he produced theatre works at a terrific rate, and for 15 years he was the dominant voice of Italian opera. His major successes included The Italian Girl in Algiers (1813), The Barber of Seville (1816), La Cenerentola (1817), and Semiramide (1823).

Into the genteel atmosphere of lingering 18th-century operatic manners, Rossini brought genuine originality marked by rude wit and humor and a willingness to sacrifice all “rules” of musical and operatic decorum. His career marked the zenith of the bel canto style, a singer-dominated manner of composition that emphasized vocal agility and long, florid phrasing.

Across a span of 20 years, Rossini wrote 39 operas, five of them in 1812 alone. Though the Italian composer retired from composing operas at age 37, and lived to be 76, his musical legacy lives on.

The Italian Girl in Algiers was composed in typical Rossini fashion: quickly, in less than a month. The composer conducted the premiere of the work that he called a melodrama giocoso in Venice in May 1813.

The Overture begins with a slow introduction that features an ornamental (quasi-exotic) solo for oboe, and is followed by an allegro with a main theme in the winds. A contrasting idea is a perky yet sinuous tune sung by an oboe, then flute. And, very much present and accounted for is a pulse-quickening episode that takes off like a locomotive getting up steam, that is, it gets faster and louder as it goes – a Rossini trademark for which the composer was both praised as well as damned.

No list of Rossini’s greatest hits would be complete without the famous overture from his final grand opera, William Tell. This lively song has been featured (and parodied) in countless television shows, movies, and commercials, and is perhaps most widely known as the theme song for The Lone Ranger.

“Largo al factotum” from The Barber of Seville (1862)

The story follows the escapades of a barber, Figaro, as he assists Count Almaviva in prising the beautiful Rosina away from her lecherous guardian, Dr Bartolo.

The opera’s best known aria, ‘Make way for the servant who does everything’ (‘Largo al factotum’) is sung by the title character, Figaro, on his entrance. Figaro sings his own praises – ‘bravo Figaro, bravo, bravissimo!’ – and shows how in demand he is!

If you sing the name “Figaro” to just about anyone on the street, there’s a pretty good chance they’ll respond with “Figaro! Figaro! Fig-aaa-roooooh!”

Rossini’s The Barber of Seville remains a mainstay in popular culture thanks to its inclusion in countless commercials, blockbuster films, and cartoons.

A Comic Duet for Two Cats, is a popular performance piece for two sopranos and piano. Often performed as a comical concert encore, it consists entirely of the repeated word “meow” sung by the singers. While the piece is typically attributed to Gioachino Rossini, it was not actually written by him, but is instead a compilation written in 1825 that draws principally on his 1816 opera Otello. It is claimed that the compiler was Robert Lucas de Pearsall, who for this purpose adopted the pseudonym “G. Berthold”.