The Violin

The Violin

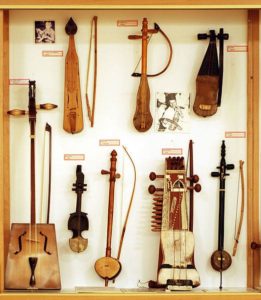

Bowed string instruments have been played all over the world for many thousands of years. Medieval instruments including the Chinese erhu, the Finnish bowed lyre and the Indian sarangi all had the same basic mechanics as the modern violin, using the principle of a continually resonating string amplified by a hollow body.

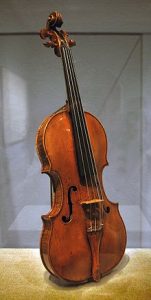

Compared to its ancestors, the violin is in a class by itself in terms of completeness. In addition, it was not improved gradually over time, but appeared in its current form suddenly around 1550. Yet, none of these early violins exist today. This history of the violin is inferred from paintings from this era that feature violins. The two earliest violin makers in recorded history are both from northern Italy: Andre Amati and Gasparo di Bertolotti. With these two violin makers, the history of the violin emerges from the fog of legend to hard fact. Violins produced by these two still exist today.

This violin, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, may have been part of a set made for the marriage of Philip II of Spain to Elisabeth of Valois in 1559, which would make it one of the earliest known violins in existence.

Bach: Partita #1 in E Major: Gavotte (1731)

This Partita is the last of a set of six pieces for unaccompanied violin — three sonatas and three partitas. Bach’s works were usually composed for some particular occasion or to fulfill a commission, but no such motive seems to have existed for the works of Op. 12. They may have been composed as a showcase for the talents of the principal violinist of the orchestra at Cöthen. The partitas demonstrate an intimate knowledge of the violin’s typical idioms and performing techniques. They

also show Bach’s extraordinary ability to create complex counterpoint, rich harmony and interesting rhythms without an accompanying bass part.

Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 9 “Kreutzer” Opus 47 (1804)

This is the longest, and most complex, of Beethoven’s 10 violin sonatas, regarded as the pinnacle of violin sonatas. At the first performance, with Beethoven on piano, the violinist George Bridgetower sight-read the score, because Beethoven only finished it the night before. What makes this piece stand out among other things, is the prominence of the piano. It is said that Beethoven intended to write this piece for the piano, with the violin as an accompaniment. Nevertheless, in the violin repertoire this type of sonata is considered to be one of the violin sonatas, because the violin appears to have the leading melody. Everything aside, the real art lies within the question-and-answer relationship of the instruments and the amazing harmony it creates.

Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 (1844)

Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 (1844)

Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto in E minor is regarded as one of the greatest violin concertos of all time and is one of the most popular and frequently performed violin concertos in history. Although the concerto consists of three movements, and each movement follows a traditional form, the concerto was innovative and included many novel features for its time. Distinctive features include the almost immediate entrance of the violin at the beginning of the work and the through-composed form of the concerto as a whole, in which the three movements, each following the previous one without any pauses, are melodically and harmonically connected.

Brahms: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 77 (1878)

Johannes Brahms’ Violin Concerto in D major is one of the most beautiful and challenging violin concertos written. This piece is typical Brahms and takes the audience on an emotional journey through love, sorrow, and happiness.

Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 35 (1878)

Tchaikovsky only wrote one violin concerto. It seems as though he had no intention of making another one and therefore put all his inspiration and energy into this one. Whatever the cause may be, it doesn’t get much better than this. What is special about this concerto is that the level of difficulty is above that of most other concertos. Mendelsohn, Bruch and even Paganini will not compare to Tchaikovsky. This does become understandable when you hear the fast octaves, double stops, flying spiccato, tenths, and 4-note chords in all positions, not to mention the extreme amount of romance in the second movement which requires exceptional phrasing to do it justice. Your fingers will be in a world of suffering trying to get the tricky parts, as Itzhak Perlman himself said.

Sarasate: Zigeunerweisen (1878)

Everyone violinist’s dream party piece. Sarasate’s fiendish, exciting encore number is almost custom-built for finishing a concert and as such is renowned for its fireworks.

The Viola

The Viola

One of the first questions any viola player is asked when they say that they play viola is: What is a viola? Is it a smaller violin? Is it a bigger violin? Generally only those who have played in an orchestra or are a close patron of the orchestra truly know what a viola is. In the classical string instrument family, the viola is the mysterious, underrated middle child. It sits between the violin and the cello and is often overlooked, especially during a piece where the piercing fervor of the violin and the rich magnitude of the cello tend to swallow the mellow middles. Yet, with a dark and full timbre, the viola manages very well in supporting a symphony. Without it, the ensemble would fall flat and sound noticeably hollow. As such, the viola is often cast as a significant harmonic role rather than a melodic one by composers.

Differences between violin and viola

(1) The difference in size between the violin and viola is likely to be the first thing you notice. The violin is smaller than the viola, sometimes by up to 25%.

(2) When you hear the two instruments played, you immediately know which is which. The viola has a deeper, mellower sound that sets it apart from the violin. Due to its size and the C string, the viola can play four steps lower than a violin.

(3) A viola is a mid-range instrument that uses Alto Clef for notation. That means you have to learn the Alto Clef which is unique to the viola. The violin is a higher range instrument which is played in Treble Clef. It’s the highest range of the stringed instruments.

Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante, K. 364 (1779)

Mozart was one of the first composers to liberate the voice of viola by writing six string quintets featuring two violas. This Sinfonia Concertante was written for solo violin, solo viola and orchestra. The solo viola is given the same role as the solo violin. In the slow movement, Mozart gave the viola an opportunity to show off its warm, dark singing character.

Berlioz: Harold in Italy (1834)

In 1833, Niccolo Paganini, one of the most important violinists in the history of music, acquired an extraordinary Stradivarius viola and asked Berlioz to write him a piece. However, Paganini was disappointed when he saw the draft of Berlioz’s writing (based on Lord Byron’s poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, remarking, “I expected to be playing continuously.” Berlioz had made the piece more like a symphony with some passages featuring the solo viola. Paganini kindly declined to perform the piece. However, when he heard a performance of the work five years later, he was so overwhelmed he got on his knees and kissed Berlioz’s hands in front of the audience. A few days later, he sent Berlioz a letter of congratulations, and a bank draft of 20,000 francs.

Schumann: Marchenbilder, Op. 113 (1851)

This work is comprises of four short pieces for viola and piano, and the title translates to Fairy Tale Pictures. The viola is used with great imagination to suggest in turn a melancholy meditation, a scenario of heroic endeavor, an agitated confrontation and a lullaby with slightly sinister undertones – this last memorably exploiting the unique sound of the viola’s lowest string. Schumann didn’t leave any trace of what the fairy tale stories might be, but the music itself is so imaginative that it’s easy to make up your own stories.

This is a work that really put composer William Walton on the map. His Viola Concerto quickly became an established part of the instrument’s repertoire, from its melancholy opening to the infectious rhythms of the Scherzo.

Britten: Lachrymae, Op. 48a (1950)

Subtitled ‘Reflections on a Song of John Dowland’, Lachrymae was originally written in 1950 for viola and piano. Britten recast the piano part for string orchestra in 1976 and this is the version heard here – one that is wonderfully effective, especially near the end when the Dowland song steals in. This finely balanced performance sustains the sombre mood beautifully.

I’m returning to the violin for the final piece of the week.

I’m returning to the violin for the final piece of the week.

For all the moments of movie bombast he’s soundtracked over the years, it’s actually for one of his quieter moments for which John Williams is rightfully respected. This haunting, folksong-like melody is deceptively simple and, given the context of Steven Spielberg’s film, absolutely heartbreaking.