Frederic Chopin was a Polish-born pianist and composer of matchless genius in the realm of keyboard music. As a pianist, his talents were beyond emulation and had an impact on other musicians entirely out of proportion to the number of concerts he gave — only 30 public performances in 30 years. No one before or since has contributed as many significant works to the piano’s repertoire, or come closer to capturing its soul.

Frederic Chopin was a Polish-born pianist and composer of matchless genius in the realm of keyboard music. As a pianist, his talents were beyond emulation and had an impact on other musicians entirely out of proportion to the number of concerts he gave — only 30 public performances in 30 years. No one before or since has contributed as many significant works to the piano’s repertoire, or come closer to capturing its soul.

Chopin was born in the small village of Zelazowa Wola, in the Duchy of Warsaw, to a Polish mother and French-expatriate father, and was a child prodigy pianist. Among the influences on his style of composition were Polish folk music, the classical tradition of JS Bach, Mozart and Schubert. His musical talents were noticed very early on: At the age of 7 he was already composing, at 8 he was performing in concerts and at 15 he received the title of “First Pianist of the City” in Warsaw.

In contrast to Mozart, whose father took him on a tour of Europe at an early age, Chopin was able to enjoy his childhood. He grew up in Warsaw, Poland, with friends his own age and enjoyed peaceful vacations.

Nocturne in B-flat Minor, Op. 9, No. 1 (1830)

Nocturne in B-flat Minor, Op. 9, No. 1 (1830)

Nocturne in E-Flat Major, Op. 9, No. 2 (1832)

Chopin was an expert in the art of writing and playing ‘cantabile’ (in a singing style), and you won’t find more charming melodies than those of the Nocturnes in B flat minor and E flat, largely considered Chopin’s most famous, from his Nocturnes Op. 9. The first has a delightful rhythmic freedom and unexpectedly docile middle section, while No. 2’s simple yet beguiling melody haunts from start to finish, inviting us into an intimate world where every note matters.

Grande Valse Brilliante in E-flat Major (1833)

The waltz was somewhat foreign to Chopin’s Polish nature. During the brief time he spent in Vienna before moving on to Paris, he wrote in a letter to his parents, “I have acquired nothing of that which is specifically Viennese by nature, and accordingly I am still unable to play waltzes.” Nevertheless, this did not stop him from gaining a proficiency in their composition or from producing melodies that could rival those of Strauss. Over the course of his career, he composed at least twenty waltzes. Unlike earlier Viennese waltzes, Chopin’s were intended for the concert stage instead of to accompany the dance.

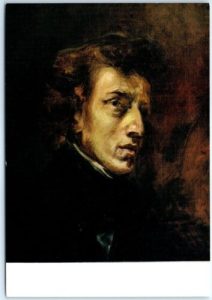

By the 1830s, Paris had become the undisputed center of European culture — a hotbed of new thinking in the arts and letters and the focal point of Romanticism in music. After a sensational debut at the Salle Pleyel on Feb. 26, 1832, with Franz Liszt, Felix Mendelssohn and Luigi Cherubini among those in the audience, Chopin, three days shy of his 22nd birthday, took his place as one of the celebrities of the French capital. He found himself in such demand as a teacher that he was able to make a comfortable living, and he hobnobbed with the great artists of the day, forming particularly close friendships with Eugene Delacroix, who would paint a splendid portrait of him in 1838, and Liszt.

By the 1830s, Paris had become the undisputed center of European culture — a hotbed of new thinking in the arts and letters and the focal point of Romanticism in music. After a sensational debut at the Salle Pleyel on Feb. 26, 1832, with Franz Liszt, Felix Mendelssohn and Luigi Cherubini among those in the audience, Chopin, three days shy of his 22nd birthday, took his place as one of the celebrities of the French capital. He found himself in such demand as a teacher that he was able to make a comfortable living, and he hobnobbed with the great artists of the day, forming particularly close friendships with Eugene Delacroix, who would paint a splendid portrait of him in 1838, and Liszt.

The posthumously published Fantaisie-Impromptu is one of Chopin’s most ostentatiously improvised works, and a fantastic show piece for the piano. While we take these ornamentations as gospel now, Chopin frequently forgot his own melismatic inventions, and would play them differently every time he performed live.

Ballade No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 23 (1835)

Chopin was only 21 when he created the first and most popular of his ballades. It is a highly dramatic piece, its ballade nature defined by its lilting rhythm and long-spun, bard-like melodies; ferocious and impassioned outbursts interrupt and transform its themes until it ends in a startling coda of stark, wild gestures. Some commentators have suggested it could be based on Adam Mickiewicz’s epic poem Konrad Wallenrod – a romantic tale, written three years before the Ballade, featuring a mysterious hero, a long-lost beloved, concealed identities, ferocious battles and a cataclysmic suicide.

Chopin suffered from great stage fright. To his friend and confidant Liszt, he wrote: “I am not fit to give concerts, me whom the public intimidates”. He prefers to play for his friends, in small committee. George Sand testified in a letter: “He doesn’t want posters, he doesn’t want programs, he doesn’t want too many people. He doesn’t want anyone to talk about it. He is afraid of so many things, that I propose to play without candles, without listeners, on a silent piano.”

Polonaise for Piano in A Major, Op. 40, No. 1, (1838)

Chopin was one of the biggest exponents of the ‘Polonaise’, the French word for ‘Polish’, writing 23 of them. The ‘Military’ Polonaise in A major, so named for its precise, forthright manner, is paired with its rather more sombre twin, the Polonaise in C minor. The former was coined by leading Chopin interpreter Arthur Rubinstein as “the symbol of Polish glory”, while the latter he named “the symbol of Polish tragedy”.

Chopin’s art reached a new plateau in the late 1830s as a result of his involvement with the writer Aurore Dudevant, six years his senior, who in 1832 had taken to calling herself George Sand. Some of his greatest works emerged as a result of the emotional contentment he felt in the early days of their nine-year liaison. They spent the winter of 1838-39 together on Majorca, living in adjacent rooms in an abandoned Carthusian monastery. Chopin endured his first major bout of tuberculosis (possibly), but though seriously ill managed to complete the 24 Preludes, Op. 28 (1838-39).

Chopin’s art reached a new plateau in the late 1830s as a result of his involvement with the writer Aurore Dudevant, six years his senior, who in 1832 had taken to calling herself George Sand. Some of his greatest works emerged as a result of the emotional contentment he felt in the early days of their nine-year liaison. They spent the winter of 1838-39 together on Majorca, living in adjacent rooms in an abandoned Carthusian monastery. Chopin endured his first major bout of tuberculosis (possibly), but though seriously ill managed to complete the 24 Preludes, Op. 28 (1838-39).

Prelude D-flat Major, Op. 28: No. 15, “Raindrop” (1839)

In Chopin’s 24 Preludes, an extraordinary piano cycle, he covers all major and minor keys and uses a circle of fifths as his guide, following each major key with its relative minor. Each prelude contains a unique idea or feeling. With these intricate musical sketches Chopin gave new meaning to the ‘Prelude’ and challenged attitudes to smaller-scale music. Musicologist Henry Finck once said: “If all piano music in the world were to be destroyed, excepting one collection, my vote should be cast for Chopin’s Preludes.”

Etude in E Minor, Op. 10, No. 13 (1839)

Etude in E Minor, Op. 10, No. 13 (1839)

Chopin’s Études, of which there are 27 in total, formed the foundations for a new style of piano playing, and comprise some of the most fiendish works ever written for the keyboard. Some have been named over time including the Op.10 No.3, which is often labelled ‘Tristesse’ (Sadness) or ‘Farewell’ (L’Adieu), but neither names were given by the composer himself, rather by his critics. Chopin held his Etude No.3 in extremely high regard, telling one of his pupils he “had never in his life written another such beautiful melody”.

Prelude in E Minor for Piano, Op. 28, No. 4

Chopin’s harmony makes a vital contribution to the brooding quality of this miniature lasting less than 2 minutes. Without the pulsating chords of its accompaniment, the melody might seem aimless and monotonous. It hardly moves, alternating obsessively between a long note and a shorter one right above it.

The situation with George Sand began to deteriorate in 1843, and in 1847 the break came. By then, Chopin was gravely ill; seeking escape, he left Paris in April 1848 for an extended sojourn in England and Scotland, from which he returned, exhausted, in November. He composed virtually nothing in the final year of his life.

The popular opinion has always been that Chopin died of tuberculosis, but I’ve recently run across information that shows that it was likely something else — possibly cystic fibrosis, possibly heart disease, possibly something else. The autopsy was carried out by Dr. Jean Cruveilhier, one of the most prominent medical authorities of the day who wrote several books on tuberculosis. The autopsy report has never been found, but in his correspondence, Cruveilhier stated that “the autopsy gave no answer as to the cause of death, but the lungs were less affected than the heart. This is a disease that I have not seen before.”

Chopin’s face is brought to life in artist’s incredible 3D portraits

“Minute” Waltz in D-flat major, Op. 64, No. 1

A delightful piano romance of trills, extensive rubato and playful dynamics, the ‘Minute’ waltz is deliciously fun to both play and hear. Despite its title, the ‘Minute’ waltz is so called because it is ‘miniature’, not because it should be played in a minute (mind you, that hasn’t stopped musicians giving it a go).

It was originally titled ‘The Waltz of the Little Dog’, because as Chopin was composing the music, it is so told that a little dog was running around the piano, merrily chasing its tail. Chopin nods to his canine companion’s enthusiasm in the middle section, with a series of grace notes in the right hand which represent the bell around its neck.

Chopin was the first composer of genius to devote himself uniquely to the piano — every one of his works was written for it either as solo instrument or in combination with other instruments. In his remarkably advanced treatment of harmony and rhythm, Chopin banished the ordinary from his music and opened the door to an emotional ambiguity that continues to intrigue listeners — one whose communication requires subtleties of execution that generations of pianists have labored devotedly to achieve. The luminous textures and haunting melodies he used to express his thoughts added to the piano’s sound and range of color shadings that no one before him had imagined were there, but that all who have followed recognize as his. He created a slimmer oeuvre than his important contemporaries, but every piece he produced was a pearl.