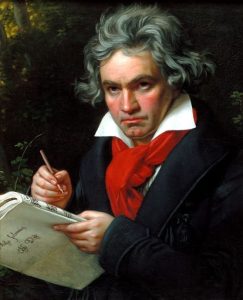

Ludwig van Beethoven is one of the most influential and significant composers of all time. He was the predominant musical figure in the transitional period between the Classical and Romantic eras and, despite suffering far reaching medical and emotional torments (he became completely deaf by the age of 40), his music is a testament to the human spirit in the face of cruel misfortune.

9 Variations on a March by Ernst Dressler in C minor (1782)

9 Variations on a March by Ernst Dressler in C minor (1782)

This is Beethoven’s first documented composition, written when he was only 12 years old. Not many 12-year-olds can compose anything at all of worth, let alone a dense and layered theme and variations, but Beethoven obviously wasn’t most 12-year-olds . . .

The young Ludwig Van Beethoven wasn’t as much of an extrovert as Mozart, but his early compositions were every bit as ingenious as his predecessor’s.

Beethoven was born in the Rhineland city of Bonn on December 16, 1770. His enormous talent was recognized early, and his father, Johann, did his level best to beat his son into becoming a prodigy to rival Mozart. (Mozart was only fourteen years Ludwig’s senior.) In this Johann failed. What he succeeded in doing was to make his son hate his father pathologically and, by extension, anyone he perceived as an authority figure.

Beethoven despised aristocrats and, protected by his celebrity, took perverse pleasure in telling them so. After a quarrel with Prince Lichnowsky, a patron, he wrote. “Prince, what you are, you are by accident of birth; what I am, I am of myself. There are and there will be thousands of princes. There is only one Beethoven.”

String Quartet in F Major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1798-1800)

String Quartet in F Major, Op. 18, No. 1 (1798-1800)

Joseph Haydn was the original string quartet pioneer, establishing the genre in a remarkable series of works that reached first maturity in 1771. There were slews of Haydn imitators, but history has winnowed our awareness down to the few of startling originality and expressive power. First Mozart. Then Beethoven. In an odd parallel to Mozart, Beethoven, around 28, freshly relocated in Vienna, turned to the string quartet for the first time.

He worked painstakingly for two years to produce his first string quartets, Op. 18, published in 1801 in the fashion of the time as a set of six.

Antonio Salieri has a bad rap in many a mind, thanks to insidious rumors about his distaste for Mozart which were bolstered by his characterization in the film Amadeus. But he was a talented composer in his own right, and can take some credit for being a teacher to Beethoven himself. When Ludwig went to Vienna, he sought instruction from the Italian composer. From Salieri, Beethoven learned the art of vocal music.

Beethoven’s own pupil, Carl Czerny, tells an interesting anecdote from that time. Once, Salieri had some negative feedback for one of Beethoven’s songs, but admitted he just couldn’t get it out of his head. Beethoven’s reply? “Then, Herr Salieri, it cannot have been so utterly bad!”

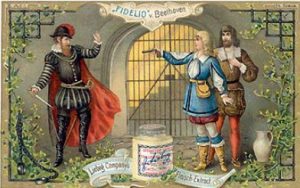

Beethoven’s only opera . . . and it took him three versions (and four overtures) to get it right. Fidelio is a love story – a wife disguises herself as a boy to get a job at the jail where her husband Florestan is imprisoned, and engineers his release – and the story of freedom triumphing over oppression.

Beethoven was a hopeless romantic and fell in love many times with women who ultimately rejected him. He proposed marriage to three different women, each of whom turned him down. He had very few friends, because he usually managed to insult or upset them.

Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor for Piano, Op. 27, “Moonlight” (1801)

Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor for Piano, Op. 27, “Moonlight” (1801)

The year 1801 marked not only the dawn of a new century, but also a significant new approach on Beethoven’s part to matters of form and structure in the piano sonata. The bold use of unusual and exotic keys, quasi-programmatic elements, irregular forms and unorthodox ordering of movements all contributed to heralding a new note in Beethoven’s sonatas.

The subtitle, “Moonlight”, was not given by Beethoven. It came from the German critic and poet Ludwig Rellstab, who once commented that the first movement made him think of “a vision of a boat on Lake Lucerne by moonlight.” In point of fact, the composer never saw the Lake of Lucerne, and in any case, the mood ascribed to the sonata fits only the first movement. Furthermore, Beethoven never even heard of the appellation “Moonlight” Sonata, as it was not affixed until five years after his death.

Sorry to say, but Beethoven was a klutz. One of his contemporaries remembered, “His clumsy movements lacked all grace. He seldom picked up anything with his hand without dropping it or breaking it. No furniture was safe from him, least of all a valuable piece; all was overturned, dirty and destroyed.”

The same went for his pianos. On several occasions, he upset his inkwell into the piano. And he was often breaking piano strings with his exuberant playing. His biggest requirement of a piano was that it be “sturdy.”

Another acquaintance mused, “How he managed to shave himself is hard to understand, even making allowance for the many cuts upon his cheeks. And he never learned to dance in time to the music.”

Beethoven acknowledged this, writing to the composer Ferdinand Ries: “Beethoven can write music, thank God, but he can do nothing else on Earth.”

Symphony No. 3 in E flat, op. 55 – “Eroica” (1803)

Symphony No. 3 in E flat, op. 55 – “Eroica” (1803)

In 1803, Beethoven completed his masterful third symphony. It’s big and bold, and from those striking opening chords the audience knows it’s in for something impressive.

So it was only appropriate that this magnificent symphony be dedicated to someone of equal importance. And who better than to dedicate your best work than to your idol? For Beethoven, there was no question that his own hero, Napoleon Bonaparte, should be the dedicatee. At least, until he realized his own personal hero was a maniacal dictator bent on world domination.

When he learned Napoleon had declared himself emperor, Beethoven lamented, “[Napoleon] is nothing but an ordinary being! Now he will trample the rights of man under foot and pander to his own ambition.” Beethoven scratched out Napoleon’s name from the dedication page, tore it up, and retitled it “Sinfonia Eroica,” for the true heroes of the world.

Beethoven was sort of a slob and he looked totally crazy at times, waving his arms, composing in his head, and shouting to be heard. In fact, he once got arrested by the police when he got lost in the suburbs of Vienna and he started peeking in people’s windows to try to orient himself. A local musician had to be brought into the police station to identify him.

Piano Sonata No. 21, “Waldstein” (1804)

The Waldstein piano sonata was dedicated to Beethoven’s patron in Bonn, back in his teenage years. It begins with a joyous first movement, with rapidly repeated chords at the opening – a challenge for the pianist. It’s followed by a mysterious slow movement, before the final movement takes flight with a glorious soaring theme — an answer to those who say his music is always angry.

A well-known tale that pops up in almost every biography goes like this: While playing a private piano recital for one of his royal patrons, Beethoven happened to glance at the audience and noticed a certain Count Palffy chatting with a woman, paying no attention to the music. Beethoven stopped playing, slammed his fists on the keyboard, shouted at the audience “I won’t play for swine!” and stormed out.

Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 65 (1808)

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 is one of the most frequently performed symphonies and one of the best-known compositions in classical music. The symphony begins with a distinctive four-note opening motif, that recurs in various forms throughout the work, which Beethoven allegedly described to his secretary and biographer Anton Schindler as “Fate knocking at the door”.

The fifth spoke a musical language no one had heard before. Paul Bekker, a German music critic, noted, “In Beethoven, a composer arose who completely understood the possibilities of the art. He knew the secret forces of his spiritual kingdom. He was artist enough to enforce his will.”

Heiligenstadt Testament

The Heiligenstadt Testament is Beethoven’s famous letter written to his brothers in 1802. In the letter the composer puts on paper his frustration with his growing hearing problem, at the same time attributing his gradual withdrawal from people to this illness. In the letter he also plays with the idea of suicide.

“Oh you men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me. You do not know the secret cause which makes me seem that way to you. From childhood on my heart and soul have been full of the tender feeling of goodwill, and I was ever inclined to accomplish great things. But, think that for 6 years now I have been hopelessly afflicted, made worse by senseless doctors, from year to year deceived with hopes of improvement, finally compelled to face the prospect of a lasting malady (whose cure will take years, or perhaps be impossible). Though born with a fiery, active temperament, even susceptible to the diversions of society, I was soon compelled to withdraw myself, to live life alone. If at times I tried to forget all this, oh how harshly was I flung back by the doubly sad experience of my bad hearing. Yet it was impossible for me to say to people, “Speak louder, shout, for I am deaf.”

. . . forgive me when you see me draw back when I would have gladly mingled with you. My misfortune is doubly painful to me because I am bound to be misunderstood; for me there can be no relaxation with my fellow-men, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of ideas. . . I must live almost alone like an exile.

. . . Thus it has been during the last six months which I have spent in the country . . . But what a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing. Such incidents drove me almost to despair, a little more of that and I would have ended my life.

It was only my art that held me back. Oh, it seemed impossible to me to leave this world before I had produced all that I felt capable of producing, and so I prolonged this wretched existence — truly wretched for so susceptible a body that a sudden change can plunge me from the best into the worst of states.”

Symphony No. 6 in F Major, Op. 68 (1808)

Beethoven titled only two of his symphonies, and the only time in Beethoven’s symphonic career that he wrote any “program notes” occurred at the premiere of his Sixth Symphony on December 22, 1808.

“Pastoral Symphony, more an expression of feeling than painting. First piece: pleasant feelings, which awaken on arriving in the countryside. Second piece: Scene by the brook. Third piece: Merry gathering of country people, interrupted by the fourth piece: Thunder and storm, which breaks into the fifth piece: Salutary feelings combined with thanks to the Deity.” Thus, the images are specific; but possibly in his own mind a bit unnecessary.

On another occasion, he also wrote: “Anyone who has an idea of country life can make out for himself the intentions of the author without a lot of titles.” Disclaimers aside, the titles indicate exactly what is being presented, and the result is music, painting via evocation and specific nature references, which are undeniable. The choice of the countryside would have been natural for the composer. He loved his daily walks “where nature is so beautifully silent. How happy I am to be able to wander among the bushes and grass, under trees and over rocks, no man can love the country as I love it.”

Piano Trios B Flat, Op. 97 “Archduke”: Andante cantabile (1811)

This was the last piece Beethoven performed in public, due to the worsening of his deafness. Dedicated to his greatest patron, the trio has a joyous first movement, but the slow movement is one of his loveliest.

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125 “Choral” (1811)

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor, Op. 125 “Choral” (1811)

The Ninth is the culmination of Beethoven’s genius. He uses solo voices in a symphony for the first time. It is the longest and most complex of all his symphonies, which we may regard it as the pinnacle of his achievement, because it is his last symphony – but he was working on his Tenth when he died.

Symphony No. 9 is also known as the ‘Choral’ Symphony as its final movement features four vocal soloists and a chorus who sing a setting of Schiller’s poem An Die Freude (Ode To Joy). In this symphony, Beethoven took the structure of a classical symphony to its limits in expression of his lofty philosophical theme: the unity of mankind and our place in the universe. Beethoven’s ‘Choral’ Symphony became a source of inspiration to composers who followed, and a keystone of the 19th-century Romantic movement.

On 24 March 1827 Beethoven sank into a coma, which lasted two days. A violent thunderstorm struck Vienna in the afternoon of March 26. At 5:45pm, a sudden flash of lightning was reported. As a biographer recounts, “the dying man suddenly raised his head, stretched out his own right arm majestically—like a general giving orders to an army. This was but for an instant; the arm sunk back; he fell back; Beethoven was dead.”

Beethoven’s music is still widely played today, from Für Elise to Symphony No. 5 to the Moonlight Sonata to Ode to Joy. It’s hard to find someone who hasn’t heard these pieces. What’s more is that nearly every development in Western art music can be traced back to the Classical Era. Beethoven himself transformed the Sonata form and brought new emotional and intellectual depth to music, inspiring many others who came after him. Contemporary music would not be what it is today without the influence of gifted composers like Beethoven. It has been said that Beethoven established the popular concept of the “artist”, a person separate from society with a profound influence over the culture. An estimated 20,000 Viennese citizens attended his funeral — quite a sum, especially for the year 1827, and a clear testament to the influence he had over his contemporaries.

Fidelio Overture (1798)

Fidelio Overture (1798)