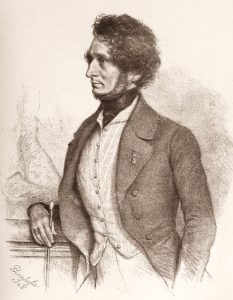

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869)

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869)

French Romantic composer Hector Berlioz wrote some of the defining Romantic works of the 19th century including Symphonie Fantastique, his most famous work. He was a composer of startling originality and one of the boldest pioneers in new orchestral sonorities.

Berlioz was also one of the strongest proponents of using literature to create a musical narrative. He is most known for developing symphonic program music and the ‘idée fixe’ where a melody or theme is used over and over to represent a person or a programmatic idea throughout an entire musical composition.

His influence was critical for the further development of Romanticism in many composers including Richard Wagner, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Franz Liszt, Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler.

Hector’s father was a well-known physician in his hometown in the French Alps and wanted his son to follow in his footsteps. At the age of eighteen, Berlioz was sent to Paris to study medicine. Although he was passionate about music, theatre, and literature, he had little interest in medicine.

In his memoir, he describes his feeling during his initial training experience: “When I entered that fearful human charnel-house . . . . such a feeling of horror possessed me that I leapt out of the window, and fled home as though Death and all his hideous crew were at my heels.”

This work is an epic for a huge orchestra. Through its movements, it tells the story of an artist’s self-destructive passion for a beautiful woman. The story is a self-portrait of its composer, Hector Berlioz.

In 1827, the 23-year-old Hector Berlioz attended a performance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in Paris; Harriet Smithson, a charismatic Irish actress, was playing Ophelia. Berlioz was smitten and wrote her an impassioned letter – Smithson did not reply. Undeterred, he continued to bombard her with messages but she left Paris without making contact.

The composer had to find an outlet for his obsessive love – naturally, that was music. He formed the idea of a “fantastic symphony” portraying an episode in the life of an artist who is constantly haunted by the vision of the perfect, unattainable woman.

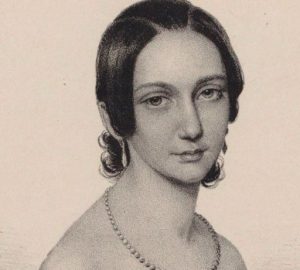

Symphonie Fantastique was premiered in 1830 but Smithson did not hear the work until 1832, when she realized she might be the inspiration for it. Intrigued, she agreed to meet the composer and was blown away by the force of his emotion. Despite neither speaking the other’s language, Harriet and Hector married on October 3, 1833. Happy ever after? Sadly, no – the obsession faded and they divorced seven years later.

Harriet Smithson

Symphonie Fantastique is cast in five movements: the first a dream, the second a ball where the artist is haunted by the sight of his beloved.

After a country scene, the fourth movement slips into nightmare: “Convinced that his love is spurned, the artist poisons himself with opium,” explained Berlioz. “The dose of narcotic plunges him into a heavy sleep. He dreams that he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned, led to the scaffold and is witnessing his own execution.”

Now everything descends into the thrillingly horrific Dream Of A Witches’ Sabbath, which weaves in the medieval Dies Irae plainchant. The artist’s perfect beloved transforms into a whore and is cast into Hell (symbolically, perhaps, for Smithson was rumored to be having an affair with her manager at the time).

Central to the work is the “idée fixe” (“fixed idea”), a recurring theme of rising longing and falling despair – a depiction of gripping obsession and the epitome of Romanticism.

The Damnation of Faust, Op. 24, Part 1 – Marche Hongroise (1845)

Inspired by a translation of Goethe’s dramatic poem Faust, Berlioz composed La Damnation De Faust during an extended conducting tour in 1845–1846. Like the masterpiece on which it is based the work defies easy categorization. Originally subtitled ‘concert opera’ and later ‘legend opera’ Berlioz ultimately called the work a ‘dramatic legend’. Berlioz’s fantastically inventive choral triumph depicts everything from love duets, drinking songs and a galloping ride to hell.

Mikhail Glinka (1804-1852)

Mikhail Glinka (1804-1852)

Considered by many subsequent Russian composers as the father of modern Russian music, Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka was something of an unlikely hero. An aristocrat and a dilettante, he became a determined reformer of Russian music through his passion for Italian and French culture. His operas, though Russian in subject, used Italian and French operatic practices as models on which to build.

Ruslan and Lyudmila: Overture (1842)

In his memoirs Mikhail Glinka recalled his early fascination with the folk songs the family’s serfs would sing. For a young aristocrat, however, a career as a composer was out of the question; so, at his father’s insistence, Glinka passed several years in the government bureaucracy. It was at that time that he became friendly with the poet Alexander Pushkin.

This opera was based on the satirical fairy tale Ruslan and Ludmila by Pushkin. Glinka hoped that Pushkin would write the libretto, but the possibility was lost when the poet, only 38 years old, was killed in a duel in January 1837. Glinka started composing the opera without a libretto, and the literary side of the project moved ahead when a fellow named Konstantin Bakhturin listened to the composer play excerpts from the score.

All St. Petersburg’s society attended the opening. Instead of using his native Russian style, the opera’s musical ideas were taken from Persia, Turkey and states bordering Russia. This exoticism fazed the audience, and the plot, which reflects Pushkin’s idea of the rulers-to-be having to endure severe trials before attaining their thrones, caused the Tsar’s party to leave early. Under these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that Ruslan and Lyudmila failed to please.

Its more adventurous musical nature, beautiful in its own right and perfectly in tune with the fantasy element of the story, later supplied much musical food for thought to composers such as Modest Mussorgsky, Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakoff and Alexander Borodin. However, Glinka’s sense of undeserved failure left him a bitterly disappointed man.

Spanish Overture No. 2, “Summer Night in Madrid” (1848)

In the following years, Glinka became a friend and ally of Hector Berlioz, whose music he tried to promote in Russia, and he composed the occasional orchestral concert piece, such as A Night in Madrid (1851).

The following year, on the trail of the roots of Western harmony in the old modes, he returned to study in Berlin. Shortly after his arrival he suffered a seizure, died and was buried in Berlin. Four months later his remains were moved to St. Petersburg for re-interment, the ceremony presided over by the dignitaries who had ignored him and his music for over a decade.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Felix Mendelssohn was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. He is often considered the greatest child prodigy after Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

In his music Mendelssohn largely observed Classical models and practices while initiating key aspects of Romanticism. Mendelssohn enjoyed early success in Germany and was well received in his travels throughout Europe as a composer, conductor and soloist. Mendelssohn wrote symphonies, concertos, piano music and chamber music.

Mendelssohn’s short life for the most part justified his name, Felix, which means “happy, lucky” and from which we get the word “felicitous.” His life showed little of the storms that marked Beethoven’s life or the stresses of Berlioz.

Born into a wealthy banking family, Felix showed an early aptitude for music. Fortunately, he had parents willing to let him become a musician, and he received the finest training.

In 1829, Mendelssohn organized and conducted an acclaimed performance of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, which had by then been quite forgotten. The success of the performance – the first since Bach’s death in 1750 – played an important role in reviving Bach’s music in Europe.

The 1840s found him splitting his time between Berlin and, more importantly, Leipzig. Through his directorship of the Gewandhaus Orchestra and his establishment of a conservatory (1843), he quickly made Leipzig one of the major European musical centers. He also continued to conduct, compose, and tour.

This amount of overwork, as well as the death of his beloved sister Fanny, led to a series of strokes and finally death at the age of 38.

Symphony No. 4 – Italian Symphony (1833)

Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 4 in A major, known as the Italian Symphony, is so named because it was intended to capture the composer’s impressions of Italy. Its inspiration was the color and atmosphere of Italy, during Mendelssohn’s Italian tour in 1830-1831.

Mendelssohn completed the symphony in Berlin in 1833 in response to an invitation for a symphony from the London (now Royal) Philharmonic Society. The symphony’s success, and Mendelssohn’s popularity, influenced the course of British music for the rest of the century.

Mendelssohn’s classic art song, On Wings of Song is a setting of a poem by Heinrich Heine. The sublime melody has become part of the repertory of musicians of every type — flutists perform the vocal line with the original piano accompaniment, pianists perform Liszt’s transcription for solo piano, and violinists play Heifitz’s setting for violin and piano. The text of Heine’s love poem describes the power of melody to transport a pair of lovers to a magical garden.

The concert overture “The Hebrides”, also known as Fingal’s Cave, was composed by Mendelssohn in 1830 and is one of his best-known works. The composition was inspired by the composer’s visit to Fingal’s cave, on the island of Staffa, in the Hebrides islands located off the west coast of Scotland. The Hebrides Overture is thoroughly evocative of the sea and the scenery Mendelssohn experienced during his time in the Hebrides and Fingal’s Cave.

Fanny Mendelssohn (1805-1847)

Fanny Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg in 1805 and learned to play the piano when she was a child. She was such an impressive young musician that the composer Carl Friedrich Zelter said of her: “This child really is something special”. But Fanny wasn’t just a brilliant performer, she was also a composer – like her younger brother Felix.

You may have noticed that the history of classical music is dominated by male composers – and Fanny’s father was a firm believer that composition wasn’t a career for women. He said to his daughter: “Music will perhaps become [Felix’s] profession, while for you it can and must be only an ornament.”

But Fanny was brimming with musical ideas and carried on composing regardless. While her brother was supportive, he also didn’t think Fanny should publish her music. He once said: “From my knowledge of Fanny I should say that she has neither inclination nor vocation for authorship. She is too much all that a woman ought to be for this.”

Overall, Fanny wrote 460 pieces of music including many ‘Songs without Words’, a type of piano piece for which her brother later became famous. Musicologists now believe Fanny pioneered this musical form.

Even today works that were thought to have been written by Felix are being re-attributed to their real composer: the great Fanny Mendelssohn.

Many of Fanny Mendelssohn’s pieces were small in scale – not because of a lack of ambition on her part, but because of her position in society. Her brother was afforded the opportunities to travel and present his orchestral works in a concert hall setting, whereas Fanny was expected to lead a domestic life entertaining the members of the correct social circle.

Having married the Prussian court painter Wilhelm Hensel, she began to host a series of successful salon concerts on Sundays, with well-known composers like Franz Liszt and Clara Schumann often attending. Short pieces like this thoughtful Notturno would have often been heard at these gatherings.

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Robert Schumann is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. The originality of his work pushed at emotional, structural and philosophical boundaries. Schumann’s music is largely programmatic, meaning it tells a story (through music, not specifically through words).

Through the 1830s Schumann wrote a vast quantity of piano music. He devoted the year of 1840 almost exclusively to songs. He next turned his attention to chamber music. Between 1841 and 1842 he wrote three string quartets, a piano quartet and a piano quintet of sheer genius. As time went on, he attempted larger forms – choral works, the opera Genoveva and four symphonies. Schumann’s musical influence extended decades into the future – his impact on Brahms, Liszt, Wagner, Elgar and Fauré.

Schumann became a composer because he failed as a pianist. The 1830s were the dawn of a new kind of piano virtuosity, exemplified by Chopin and Liszt. Schumann was eager to make his mark, and to try to speed up the process he constructed a weird device using a cigar box and some wire. It was intended to prop up his fingers while practicing, the idea being to strengthen them and develop independence. But instead, two fingers on his right hand were permanently injured.

Schumann’s constitution was never strong. He contemplated suicide on at least three occasions in the 1830s, and from the mid-1840s on he suffered periodic attacks of severe depression and nervous exhaustion. His musical powers had also declined by the late 1840s. By 1852 a general deterioration of his nervous system was becoming apparent. In 1854 he asked to be taken to a lunatic asylum. He was removed to a private asylum where he lived for nearly two and a half years, able to correspond for a time with Clara and his friends. He died there in 1856.

Carnaval is a set of twenty captivating piano miniatures representing masked revellers at Carnival, a festival before Lent, including musical portraits of Paganini and Chopin. Carnaval showcases virtually all of the young Schumann’s personal and musical characteristics in one form or another and a number of the pieces are musical portraits of the composer’s friends and important contemporaries.

Piano Quintet in E Flat Major (1842)

Schumann’s Piano Quintet In E Flat Major is considered one of his finest compositions and a major work of nineteenth-century chamber music. The quintet was dedicated to Clara (though the work was premiered with Felix Mendelssohn at the piano, instead). This work is notable for being the first work for what we know as the piano quintet (a string quartet with piano). So basically, Schumann invented an entire new genre of chamber music with this piece.

Clara Schumann (1819-1896)

Clara Schumann née Wieck was born in Leipzig, Germany, to a talented singer mother and a difficult and domineering father who was nonetheless a piano teacher of high repute who pushed her to become a child prodigy. At 14, she gave the premiere of her own Piano Concerto, with Mendelssohn conducting. By 18, she had become one of the leading virtuosos in Europe.”

She first met Robert Schumann when he came to study with Mr. Wieck in 1830. In 1840, Clara and Robert married, over Wieck’s strenuous objections.

As the primary breadwinner, Clara Schumann toured and gave concerts virtually her entire life. She set new standards of performance that continue to this day, including the playing of recitals and concertos from memory. In her recitals, she promoted contemporary composers, particularly her Robert and young Johannes Brahms.

Over the years, she gave 238 concerts with violin titan Joseph Joachim throughout Germany and England. It was through Joachim that the Schumanns first met Brahms, who became very close to the Schumann family.

When Robert Schumann’s mental health deteriorated later in life and he was admitted to an asylum, Brahms came to stay at their home to support the family. Clara and Brahms’ relationship blossomed to more than friendship, and although it’s unclear what exactly went on, this love triangle holds a position as one of the most retold love stories in music history.

Three Romances for violin and piano, Op. 22

Romances were one of Clara Schumann’s favorite forms to compose in, and these are some of her most exquisite. She toured the piece and played it before royalty with its dedicatee, her close friend and violin virtuoso, Joseph Joachim.

One critic said at the time: “All three pieces display an individual character conceived in a truly sincere manner and written in a delicate and fragrant hand.”

The Hebrides Overture (1830)

The Hebrides Overture (1830)