Mozart was born in 1756 in Salzburg, Austria. He was an extraordinary child prodigy, the prodigy by whom we measure prodigies to this day: playing harpsichord and violin at four, composing dances at five, touring Europe at six.

He settled permanently in Vienna in 1781, and died there ten years later in 1791. It was a ten-year period of perhaps unparalleled musical creation. During those years, he wrote seventeen piano concertos, a huge amount of chamber music, a Mass, a requiem, ballet music, dance music, marches and songs, as well as seven symphonies, each of them a certifiable masterwork.

Along the way he got married; fathered seven children (two of whom survived into adulthood); performed as a pianist, violinist and conductor; maintained a successful teaching studio; traveled widely; attended the theatre religiously; and rode horseback for exercise. Not bad for someone portrayed as a giggling idiot in the movies.

Minuet in G Major, KV – 1 (1761)

Minuet in G Major, KV – 1 (1761)

We all know that Mozart was a genius – but just how early did he start showing signs that he was better than your average child prodigy?

His first documented composition, the Minuet and Trio in G major, listed as KV 1 (he eventually made it all the way up to KV 626, his Requiem) and was composed when he was just five years old.

In 1763, German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe saw Mozart in concert in Frankfurt. Mozart was 7, Goethe 14. Much later in life, Goethe addressed the subject of genius, defining it as the ability to consistently produce works that “have consequences and lasting life,” adding “all the works of Mozart are of this sort.” He compared Mozart’s genius to that of William Shakespeare and Italian Renaissance artist Raphael, describing it as “unreal.”

Goethe wasn’t the only historical luminary taken with Mozart’s gifts. Austrian composer Joseph Haydn, who was 24 years Mozart’s senior and a tutor to both him and Beethoven, told Mozart’s father, “before God and as an honest man,” Wolfgang was the “greatest composer” he’d ever encountered, either in person or through published music.

Concerto for Flute and Harp KV 299: 2nd movement (1778)

Concerto for Flute and Harp KV 299: 2nd movement (1778)

When Mozart wrote this concerto in 1778, the harp was still being developed. This is the only piece of music he wrote for the instrument, but the writing for each soloist is carefully crafted. It’s something of a showpiece for harpists who can get their fingers round the difficult passages.

Though often performed as a stand-alone work, Laudate Dominum forms a single movement of Mozart’s Vesperae Solennes de Confessore, K. 339.

This was Mozart’s final composition for the Salzburg Cathedral in 1780, before departing his hometown in search of greater artistic opportunities in Vienna.

In a not-Mozart-related comment, I want to take a moment to talk about Cai Thomas, the boy in the above recording, which was made in 2019. Many boy sopranos do not end up with equally lovely adult voices. Cai is one of the lucky ones. Here is the first recording of his new baritone voice singing Der Lindenbaum by Franz Schubert.

Piano Concerto No. 11 in F major, K. 413 (1782)

Mozart wrote this concerto for a skilled pianist friend, and it shows! The elegant style of this concerto requires the touch of an expert musician. Singing melodies float about, decorated with turns, runs, and other virtuosic ornaments . . . and the simplicity exposes any weakness in the pianist’s technique. Mozart himself was a fan of this work, and he performed it many times himself.

The pianoforte in this picture was Mozart’s actual piano.

Arguably one of the most beloved and surely one of the most recognizable pieces of classical music, Eine Kleine Nachmusik’s origins remain a mystery. ‘A little night music’ is the direct translation from the German, but in Mozart’s day, Nachtmusik indicated a serenade. Normally this sort of serenade was intended for a social occasion, but there is no record of such an event. Written in the middle of composing Don Giovanni, it was not published until after Mozart’s

death, sold in a lot by his widow for needed cash. The instrumentation is for string quartet and added bass but is typically played by string orchestras.

Don Giovanni – Commendatore Scene (1787)

Don Giovanni – Commendatore Scene (1787)

Usually known for his lighthearted music, here Mozart provides an opera which, while containing comic elements, qualifies as a genuine tale of horror

In Mozart’s version of the story of Don Giovanni (Don Juan), crime and punishment bookend the opera. At the very beginning of act 1, the don kills a father attempting to defend his daughter’s honor. At the very conclusion of act 3, the dead father appears in the guise of a statue. The statue offers the don a chance to repent for his sins, and when the don refuses, the statue drags him down to hell.

Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550 (1788)

Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550 (1788)

The decline in Mozart’s fortunes that so darkened the last years of his life was well under way in the summer of 1788 when he composed the G minor Symphony. The very fact that this was one of his last symphonies tells its own tale.

This dark but temperamental piece is a good place to start when entering the world of Mozart symphonic output. Contrary to other forms, the composer struggled with the symphony form, and mostly his later symphonies (No. 38 onward) are considered truly masterful works.

Piano Sonata No 16 K 545 in C major (1788)

This Sonata was described by Mozart himself in his own thematic catalogue as “for beginners,” and it is sometimes known by the nickname Sonata facile or Sonata semplice.

Mozart added the work to his catalogue on June 26, 1788. The exact circumstances of the work’s composition are not known. Although the piece is very well known today, it was not published in Mozart’s lifetime, first appearing in print in 1805.

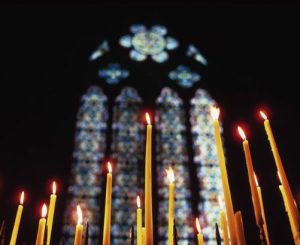

Requiem in D Minor, K. 626: Confutatis and Lacrimosa (1791)

Requiem in D Minor, K. 626: Confutatis and Lacrimosa (1791)

One of Mozart’s absolutely last pieces, this unfinished work took hold of listeners ears and many storytellers’ imagination. In all likelihood composed after a commission by a wealthy connoisseur (that used to take credit for other composers’ works), Mozart treats this classic “death mass” text like no other composer before him. Mozart favorite pupil, Franz Xaver Süssmayr, completed the score, adding orchestral parts and even complete movements, the extent of which is still debatable. In any case, this is a piece any “Mozart beginner” should explore.