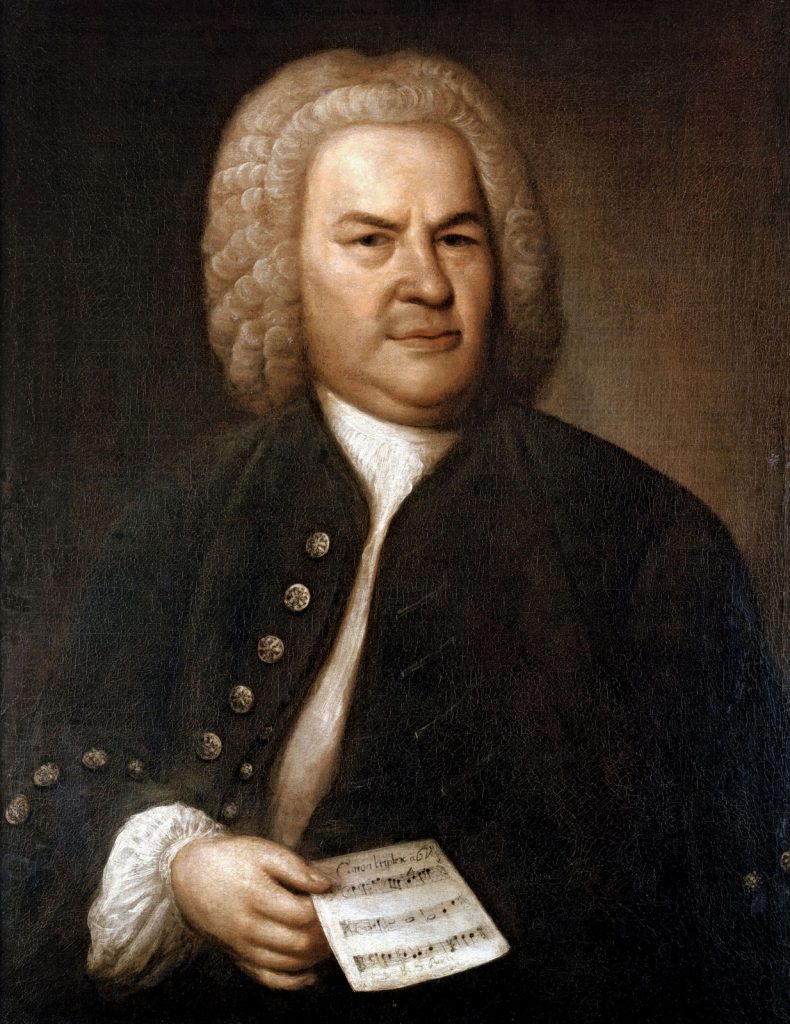

Johann Sebastian Bach, was composer of the Baroque era, the most celebrated member of a large family of north German musicians. Although he was admired by his contemporaries primarily as an outstanding harpsichordist, organist, and expert on organ building, Bach is now generally regarded as one of the greatest composers of all time. Appearing at a propitious moment in the history of music, Bach was able to survey and bring together the principal styles, forms, and national traditions that had developed during preceding generations and, by virtue of his synthesis, enrich them all. Visit this link for a more extended history of Bach’s life.

Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring (1715-16)

This is one of Bach’s most popular choral compositions. It was crafted around 1714-1716, Bach’s first year in Weimar. And it is the 10th movement of his famous cantata “Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben.” However, the melody of this piece was composed by Johann Schop, while Johann Sebastian orchestrated and harmonized the melody.

Bist Du bei mir (If Thou Be Near) is taken from the Second Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach.

Anna Magdalena married the widowed Bach 1721 and gave up her career as singer. She cared for his four children of his first marriage and gave birth to 13 own children of whom 7 died at very young age. Anna Magdalena outlived her husband 10 years and died 1760.

Bist Du Bei Mir is one of the most touching compositions in musical history. The text was written by an unknown poet.

English translation: “If thou be near, I go with joy to death and to my rest. O how pleasant would my end be, If your fair hands Would close my faithful eyes.”

(Bach 1772/Gounod 1853)

Charles-François Gounod’s “Ave Maria” is a curious case in music history – the result of a musical collaboration that spanned a century. The two composers were not even contemporaries. The melody of this song was crafted some 80 years after its accompaniment.

Bach published “Book 1” of “The Well-Tempered Clavier” in 1772. The “Prelude in C major” is the first piece of this collection. In 1853, Gounod’s works were published under the name “Meditation on the First Prelude of Sebastian Bach.” It has a solo violin part along with a piano portion which is based on Bach’s prelude.

Charles Gounod added words to his composition in 1859. However, the first wordings utilized were not “Ave Maria,” but a short poem by Alphonse de Lamartine, titled “Verses Written on an Album.” Gounod gifted a copy to his student Rosalie Jousset. However, the gift was intercepted by Rosalie’s mother-in-law. She found the whole situation highly inappropriate and replied to Gounod with an alternative text. It was the text of the popular Latin prayer “Ave Maria.” Gounod took the hint and subsequently adopted that verse instead.

The Brandenburg concertos are a collection of six instrumental works presented by Bach to Christian Ludwig, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt, in 1721 (though probably composed earlier).

They are widely regarded as some of the best orchestral compositions of the Baroque era.

Because King Frederick William I of Prussia was not a significant patron of the arts, Christian Ludwig seems to have lacked the musicians in his Berlin ensemble to perform the concertos.

The full score was left unused in the Margrave’s library until his death in 1734, when it was sold for 24 groschen (as of 2008, about US$22.00) of silver.

The autograph manuscript of the concertos was only rediscovered in the archives of Brandenburg by Siegfried Wilhelm Dehn in 1849; the concertos were first published in the following year.

A concerto nearly always involves a solo instrument (or combination of solo instruments) and an ensemble. The key idea is the alternation between one or more soloists and the whole ensemble, in a sort of light-hearted competition.

In the six Brandenburg Concertos, Bach explores every facet of this genre, with regard to both instrumentation and the way in which he handles the form.

All the traditionally used string and wind instruments and the harpsichord appear as soloists, the musical forms range from court dances to near-fugues, and the relationship between the solos and tutti (all) instruments is always shifting.

Together, the six concertos thus form a virtuoso sample sheet of the Baroque concerto.

Cantata No. 78 – We Hasten with Faltering, Yet Eager Footsteps (1724)

Bach’s Cantata No. 78 is based on a pre-existing chorale tune. This was a common practice for cantatas in the late Baroque era, particularly in Bach’s cantatas. Bach commonly reused previously written work, primarily because he was writing one cantata a week for sacred services.

This flute aria in particular reminds us that this cantata was written during a period of several months when Bach evidently had available to him a very fine flutist, for whom he wrote many expressive and virtuosic flute solos, including the extremely difficult ones in cantata BWV 8.

As other compositions in the Baroque period, rhythm and pulse are very constant and seem to be a driving factor. Voices and instruments are used in a seamless manner throughout the composition, perhaps one of the most defining characteristics of the Baroque period.

We hasten with weak, yet eager steps,

O Jesus, O Master, to You for help.

You faithfully seek the ill and erring.

Ah, hear, how we

lift up our voices to beg for help!

Let Your gracious countenance be joyful to us!

St. Matthew Passion – Erbame Dich (1727)

Erbame Dich is one of the most sublime and powerful corners of J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion.

The full title of this aria is Erbarme dich, mein Gott (“Have mercy Lord, My God, for the sake of my tears”).

In the drama, this aria reflects Peter’s solitary heartache in the garden after he denies knowing Jesus three times.

Aching beauty and profound sadness coexist in this music, along with a mix of other emotions which transcend description and literal meaning.

Sinfonia to Cantata No. 29 (1731)

Here is Bach’s famous Sinfonia to Cantata No. 29, “Wir danken dir, Gott, wir danken dir” (We thank you, God, we thank you).

Bach wrote Cantata 29 in 1731, by which time he was working in Leipzig and at the height of his career. Although there is a reference to “Gott” (God) in the title (and the work is based on sacred text), this is not actually a church cantata – that is, it was not written for a specific liturgical feast.

In this unusual rendition, Carey R. Meltz has created a semi “switched-on” music rendition, combining analog and digital synthesizers and strings to create a hybrid ensemble.

In his notes, Meltz states that “the work presented here, is my sincere homage to Wendy Carlos, whose 1969 Grammy Award winning “Switched-On Bach” was the album that sparked my interest in Classical music.”

Cantata 140 – Zion Hears the Watchmen’s Voices – M183 (1731)

Cantata BWV 140, Zion Hears the Watchmen’s Voice, also known as Sleepers Wake, is a church cantata by Bach. It is based on the hymn “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme” (1599) by Philipp Nicolai.

In this cantata everything revolves around the parable of the wise and foolish virgins. They wait throughout the night with burning lamps for the arrival of the bridegroom. Five of them have brought along extra oil to keep their lamp burning. The others run out of oil and go off to buy some more. The bridegroom arrives while they are away.

Orchestral Suite #3 in D, “Air on a G String” (1731)

Bach had composed 4 orchestral suites in the later period of his life, with the “Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D, BWV 1068” being his most celebrated work.

The nickname of this work was framed when August Wilhelmj, a German violinist created a piano and violin arrangement of the second movement of suite, No. 3. The piece could only be played on one string of a violin, which led to the creation of its nickname “Air on the G string.”

Goldberg Variations, BWV 988 (1739)

There’s an oft-told backstory to the composition of the Goldberg Variations. Dresden courtier Hermann Carl, Reichsgraf (Count) von Keyserlingk had trouble sleeping at night. Apparently he mentioned in J.S. Bach’s presence just how nice it would be if his bouts of insomnia could be graced by “gentle and somewhat merry music” played by his resident harpsichordist, teen prodigy Johann Gottlieb Goldberg. Bach picked up the dropped hint, made a beeline for his writing desk, and a towering masterpiece of Western music was born.

Of course, there are glaring contradictions to this story, not the least of which is the notion of the Goldberg Variations as “gentle and somewhat merry.”

Additionally, the Goldbergs were printed before Bach’s 1741 Dresden visit when the alleged quasi-commission took place.

Best evidence points to Bach’s beginning work on the variations in 1739, when J.G. Goldberg was all of twelve years old.

Probably Bach brought copies of the newly-engraved variations with him on his 1741 visit to his son Wilhelm Friedemann in Dresden. It would have been a proper gesture to present the Count with a copy, which Goldberg would have played, and thus was a sobriquet—and a story—born.

Andante from Sonata No. 2 in A Minor for Violin

Finally, I including this haunting arrangement of Bach’s Andante from Sonata No. 2 in A Minor for Violin by Chris Botti. It comes from one of my all time favorite albums, The Bach Variations – A Windham Hill Sampler, which I highly recommend to everyone!

in Eisenach, Germany