Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Overture to the Marriage of Figaro

Originally banned in Vienna because of its satire of the aristocracy, this opera became one of Mozart’s most successful works. The opera clearly illuminated the limitations of rank and privilege, showing that common sense can readily overcome wealth and power, and that genuine humility easily upstages unwarranted arrogance. The first performance had five numbers encored on the first night.

Overture – Most operas open with a purely orchestral composition called an overture or prelude. The music is drawn from material that will be heard later in the opera. The overture is thus a short musical statement that involves the audience in the overall dramatic mood.

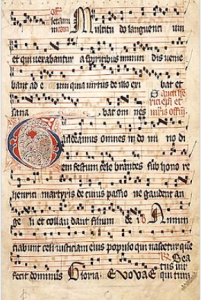

Gregorian Chant

Gregorian Chant

A simple melody sung in unison (plainchant). These are unaccompanied sacred songs in Latin used to accompany the text of the mass in the Roman Catholic Church. Gregorian chant is named after Pope Gregory I (590-604) when these songs were collected and codified. Practically the earliest form of music which we still have records of, these melodies were preserved in Catholic monasteries during the Dark Ages of Western Europe.

Anthony Holborne (c. 1545-1623)

Pavane and Galliard for the Lute

Holborne was a composer of English consort music during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. His works are the epitome of Elizabethan-age courtly grace and beauty, and, although little is known about his life, his music regularly appears in recorded anthologies of instrumental English Renaissance music.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1760)

Sheep May Safely Graze from Cantata 208

Often performed today at weddings, this is one of Bach’s best loved arias (a song for solo voice). This is an aria from a secular piece, The Hunting Cantata. The aria is sung by the character Pales, a goddess of crops, pastures and livestock.

The words are “Sheep may safely graze where a caring shepherd guards them. Where a regent reigns well, we may have security and peace, and things that let a country prosper.”

Cantata – a medium-length narrative piece of music for voices with instrumental accompaniment, typically with solos, chorus, and orchestra.

The Arrest of Egmont” by Louis Gallait, painted in the 19th century

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

In 1809 Beethoven was commissioned to compose the incidental music for a premiere of the play Egmont by Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe. This was Goethe’s free interpretation of the titular Count Egmont’s 16th-century struggle for Dutch liberty against the autocratic imperial rule of Spain. Egmont is imprisoned and sentenced to death, and when Klarchen, his mistress, fails to free him, she commits suicide. Before his own death, Egmont delivers a rousing speech and execution becomes a victorious martyrdom in a fight against oppression.

Beethoven’s incidental music begins with a powerful, strikingly original overture that summarizes the course of the drama, from its ominous slow introduction (suggesting the oppressive tread of Spain) to the manic transformation of tragedy into triumph in a brilliant ending.

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Suite Bergamasque: Clair de Lune

This is the third and most famous movement of Suite Bergamasque. Its title, which means “moonlight” in French, is taken from the Symbolist poet Paul Verlaine’s poem of the same name. The poem speaks of “au calme clair delune triste et beau” (the still moonlight sad and lovely).

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

One of the Russian composer Prokofiev’s most distinctive gifts was his flair for combining satire and sentiment. When he returned to the U.S.S.R. in the early 1930s and finally decided to settle there after many years of living in both Europe and America, he was anxious to start working on Soviet subjects. “But the musical idiom in which one could speak of Soviet life was not yet clear to me,” he wrote in his Autobiography. “It was clear to no one at this period, and I did not want to make a mistake.”

He was pleased to be offered the invitation to write the music for the film Lieutenant Kije. This was an affectionate period portrait of early nineteenth-century Russia, combined with a satire on official bungling. An office clerk in the era of the pompous Tsar Paul makes a slip when copying over official military documents. He adds a nonexistent lieutenant, Lt. Kijé, to a list of soldiers presented for the Tsar’s approval. The unusual name catches Paul’s eye, and Kijé is singled out for special treatment. So terrified are they of contradicting their sovereign that Paul’s subordinates carry out his decree, promoting the nonexistent Kijé to the Tsar’s elite guard. Kijé eventually falls into disfavor and is sentenced to Siberia. Still unaware that Kijé does not exist, and protected from the truth by his intimidated aides, the Tsar magnanimously pardons Kijé and promotes him to general. When he “dies”, Kijé is buried in an empty coffin with imperial pomp and circumstance.

Troïka is the fourth of five movements in this work. To an accompaniment suggesting the motion of the traditional Russian three-horse sleigh, complete with sleigh bells, we hear an instrumental version of a tavern song, as Kijé races across the Siberian landscape.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Tchaikovsky composed Romeo and Juliet at twenty-nine, near the beginning of his musical career. Rather than portraying the play’s events in the order in which they occur, Tchaikovsky presents a variety of characters and moods whose melodies offer effective musical contrast. The work opens with a serene clarinet-and-bassoon melody that represents the lovers’ ally, the somber and reflective Friar Laurence. The music then shifts to suggest violence, with a chaotic theme for the feuding Montague and Capulet families. Soon Tchaikovsky introduces a new melody: the soaring love theme of Romeo and Juliet themselves. As the piece progresses, love and violence share the stage with a sense of growing urgency until the love theme is reprised (repeated) in a minor key, suggesting their tragic deaths. The work concludes with a hint of Friar Laurence’s melancholy theme (in the play he arrives on the scene too late to prevent the two suicides).