The flute is the oldest woodwind instrument, dating to 900 B.C. or earlier. The first flute likely emerged in China. Early flutes were played in two different positions: vertically, like a recorder, or horizontally, in what was called the transverse position. The transverse flute first arrived in Europe with traders from the Byzantine Empire during the Middle Ages and flowered in Germany, so much so that it became known as the German flute.

The flute is the oldest woodwind instrument, dating to 900 B.C. or earlier. The first flute likely emerged in China. Early flutes were played in two different positions: vertically, like a recorder, or horizontally, in what was called the transverse position. The transverse flute first arrived in Europe with traders from the Byzantine Empire during the Middle Ages and flowered in Germany, so much so that it became known as the German flute.

During the Renaissance, it became fashionable for amateur flute players to practice and play together with what was known as “consort music” in cultured homes. The flute was an important part of these groupings. By 1600, plucked and bowed instruments were combined with flute in mixed consort music.

The piccolo is a small flute (the Italian word piccolo means small). It is exactly half the size of a standard flute, and is pitched one octave higher. It is the highest pitched instrument of the woodwind family.

It evolved at the beginning of the 19th century. Beethoven used it in Symphony no 5, and also in his 6th Symphony – the Pastoral. Tchaikovsky made extensive use of the piccolo.

Vivaldi – Piccolo Concerto in C Major, RV 443 (1711)

This concerto was one of several written while Vivaldi was working as director of music at the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice. He is thought to have written these concertos for his talented students to play, and judging by the virtuosic displays in many of his solo instrumental works, we can only assume that the overall musical quality in his department was high.

The concerto, originally written for flautino, which may have been a recorder or an early form of a piccolo, takes on the three-movement form that is common of Italian baroque style, with the bright sound of the piccolo’s high register exploited throughout.

J.S. Bach – Sonata in E Minor for Flute, BWV1034 (c. 1725)

J.S. Bach – Sonata in E Minor for Flute, BWV1034 (c. 1725)

I’m trying to resist saying “just anything by Bach” and including all his flute sonatas here (it’s tough). Honestly, we’re so lucky Bach deigned to write anything for the lowly flute as a solo instrument. This piece was written at a time when the wooden traverso flute was replacing the recorder.

In the first movement, we enter a quietly melancholy and dreamy E minor soundscape. A lamenting conversation unfolds, with the basso continuo line occasionally entering into a melodic duet with the flute. The second movement (Allegro) dances with sparkling, angelic virtuosity. The third movement (Andante) is a sensuously beautiful aria, turning to major. Dazzling fireworks erupt in the final movement with a flurry of rapid lines in the flute and a vibrant, canonic conversation between instruments.

Handel – Sonata in F Major, Op. 1, No. 11: Siciliano and Giga

It is impossible to say how many flute sonatas were composed by George Frideric Handel, but the correct number is somewhere between none and eight. There are many reasons for the confusion: some of the sonatas were originally written for other instruments, some have uncertain authenticity, some contain borrowings from other Handel works, and some were published (in an altered form) without Handel’s knowledge. At least six of the sonatas are known to contain music written by Handel, although he may not have intended some of them to have been played by the flute.

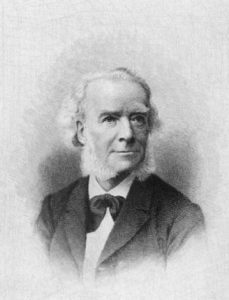

Theobald Bohm (1794-1881)

Theobald Bohm (1794-1881)

Boehm, a German wind instrument manufacturer, demonstrated a revolutionary new type of flute at the Paris Exhibition of 1847. This flute had a metal tube with numerous keys attached. With earlier flutes, it had been difficult to even get a note out of them, and the intervals between the notes had been variable. Boehm’s instrument was a dramatic improvement, however, and overcame these shortcomings. With his major refinements, Boehm essentially created the modern-day flute.

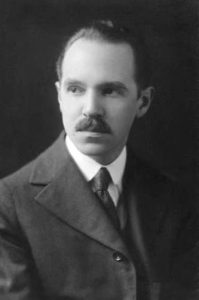

Carl Reinecke (1824-1910)

Carl Reinecke (1824-1910)

Reinecke, born June 23, 1824, in Altona (modern day Hamburg), is a highly respected composer, best known for his flute sonata Undine. He was taught by his father, and began composing at just seven years old. At age nineteen, Reinecke began his first concert tour in Copenhagen. He continued his travels until he was appointed Court Pianist in Denmark until 1848. His next appointment was in Breslau, as director of the Singing Academy. However, after his wife died in 1860, he returned to Leipzig. Reinecke unhappily spent much of his later years looking for a permanent position.

Flute Sonata “Undine”, Op. 167

Reinecke’s Flute Sonata ‘Undine’ is based off a German tale in a novel title Undine. The novel was written by Friedrich de la Motte Fouque in 1811. The story follows a water spirit Undine looking to become immortal. In order to become immortal, she must marry a mortal man. The first movement portrays Undine wandering the sea longing for a soul. In the next movement Undine, outside of her world, meets a knight named Hulbrand. The third movement illustrates their joy of the new marriage. The final movement depicts anger over the argument between Undine and Hulbrand with Undine being forced to go back to the sea. Hulbrand then remarries. Undine leaves her water world on his wedding night and gives him a kiss that kills him. She then goes to the funeral, leaving two small stream encircling the grave.

Debussy – Syrinx (1913)

Debussy – Syrinx (1913)

This is the piece that launched a thousand solo flute pieces (including mine), a genre that very few new entries in the years between Bach and Debussy. In that time, the flute transformed from a wooden instrument with just a few keys into a sleek, often silver item with full keywork. And so one of the oldest instruments became a totem of modernity.

But back to the story of this tune. In Greek mythology, and as told in Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Pan pursued the nymph Syrinx, who turned herself into a thicket of reeds by the water’s edge to escape. Pan cut the reeds to make his pipes, and that was the end of the nymph.

Truth be told, Debussy didn’t consider this an important work. To him it was a one-off. The manuscript was lost, and iwas only published posthumously in 1927 from a secondary source. Even the title is editorial: Debussy simply called it “Piece for Psyché” or Flûte de Pan, with the publisher choosing Syrinx later.

Charles Tomlinson Griffes (1884-1920)

Charles Tomlinson Griffes (1884-1920)

Griffes stands among the ranks of Debussy and Ravel, and is one of the most famous American impressionist composers. He studied piano at a young age before relocating to Berlin to continue his studies in 1903. Upon his return to the United States in 1907, the Hackley School in Tarrytown, NY appointed him the director of music, a post he held until his death in 1920. This position, while not extraordinarily creatively rewarding, offered him financial stability and time to compose.

Poem for Flute and Orchestra (1918)

The Poem for Flute and Orchestra (1918) received its first performance on November 16, 1919 by the New York Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Walter Damrosch who agreed to program the work after only hearing the piano score. While Poem has since become firmly established in the American 20th-century solo flute repertoire, it remains unique in that it demands primarily lyrical rather than technical virtuosity from the performer.

Hindemith – Sonata for Flute and Piano (1936)

Germany’s Paul Hindemith composed a delightful flute sonata in 1937 and it’s a rare gem in the repertoire. The melodies undulate around and take us to interesting places, making the instrument do things that hadn’t been heard before. It’s much less about flutey flourishes than it is about impactful note attacks and stark contrasts.

The three-movement sonata with the march at the end, which seems almost like a fourth movement, immediately became part of the standard repertoire of flutists, as did all of the sonatas which Hindemith composed for other instruments.

Hindemith completed the Sonata for Flute and Piano (1936) before resigning from his post in Berlin. He composed the work for a colleague, but the Nazi regime forbade the premiere performance, which instead occurred in America.

Francis Poulenc (1889-1963)

Francis Poulenc (1889-1963)

Poulenc had his first major successes as an 18-year-old composer without a single composition lesson. Despite some study, he remained largely self-taught. In fact, his music is so individual, it is difficult to imagine what anyone could have taught him. The music is eminently tuneful – his major strength. I regard him as a melodist fit to keep company with Schubert and Mozart. As a French songwriter, he is the great successor to Fauré.

Sonata for Flute and Piano (1957)

This sonata is as typical of Poulenc as anything he ever wrote, combining as it does elegant charm and brashness. Although titled ‘sonata,’ the piece makes no pretense of being one formally — none of the three movements is in sonata form.

The first movement’s main idea has a rather pensive character contrasted with a middle theme with an early-Debussy sweetness. The song-like middle movement is so Parisian-caféish, it could easily have (French) boy-girl-moon-June lyrics.

Having sung his tender song, Poulenc devises a virtuoso finale that is nearly all one big elbow in the ribs. Not only is the main theme as frivolous as possible, but the movement is shot through with a very brief snatch of Bach’s Badinerie (from the Suite No. 2), and quotes of the first movement’s main and secondary themes.

Everyone knows that Poulenc can be, among other things, suave, sensuous, and slapstick; the Sonata for Flute is a three-movement confirmation of this character description.

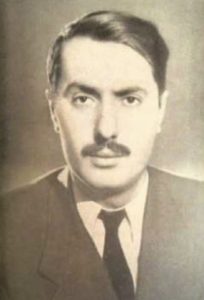

Otar Taktakishivili (1924-1989)

Otar Taktakishivili (1924-1989)

Taktakishvili was a composer, teacher, writer, and conductor in Soviet Georgia. He rose to national prominence early in his career, having composed the official anthem of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic while he was still a student at the Tbilisi Conservatory. The Conservatory later appointed him professor of choral literature and director of the choir in 1949, a mere two years after his graduation.

Sonata for Flute and Piano in C Major (1966)

Taktakishvili’s Flute Sonata is a prime example of his simple harmonic language with folk influences. It is interesting to note that this composition took 11 years to reach the United States due to the USSR’s lack of international copyright relations prior to the 1970’s.

Taktakishvili’s music often resembles Caucasus music, a broad categorization of the music of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Chechnya, and Georgia. This influence is immediately apparent in the Flute Sonata. It is unclear if Taktakishvili drew these themes from specific Georgian folk songs or if they are simply reminiscent of this particular style.

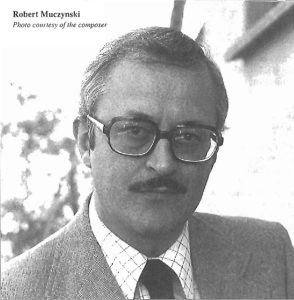

Robert Muczynski (1929-2010)

Robert Muczynski (1929-2010)

Muczynski was an American composer, pianist, and teacher, best known for his chamber music and piano works. His compositional style largely fits into the neo-classical stream, with elements of romanticism and a flair uniquely his own. His music is abstract and concise while still containing a wide range of emotion and harmonic color.

Duo for 2 Flutes, Op. 34 1973)

This is a set of duets for flutes with 6 different movements, each having a character of its own and alternating between slow and quick. The slow movements consist of haunting harmonies and obscure rhythms. In contrast, the faster movements are light, quirky, and fun! Muczynski utilizes alternating meter and unexpected placement of musical emphasis to keep the quick duets spinning forward until the end.

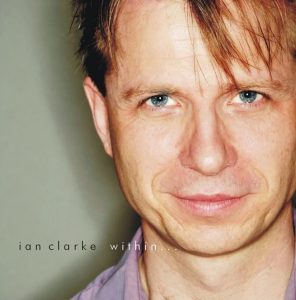

Ian Clarke (1964 – )

Ian Clarke (1964 – )

Clarke is an English composer born into a very musical family who began to teach himself to play flute at age 10. While Clarke listened to classical music in his childhood, with time, he developed an increasing interest in rock music. He graduated college with honors in Mathematics, while simultaneously playing in a rock band which he formed. Since 2000, he has been a professor of flute at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London.

We’ll end with an astonishing piece of contemporary flute music performed by a flute choir which, for once, doesn’t sound like a bunch of twittering birds.

Evoking a lonely Native American landscape, Within . . . requires pitch bends, quarter-tones, beatboxing, and alternative timbres for successful execution. This performance includes flute, piccolo and alto flute within one exciting and grooving 6-minute performance.