The organ was invented in ancient Egypt. This first organ is credited to Ctesibius, a mechanic who lived in Alexandria in the third century, B.C., who used water to make music through the organ’s pipes.

The organ was invented in ancient Egypt. This first organ is credited to Ctesibius, a mechanic who lived in Alexandria in the third century, B.C., who used water to make music through the organ’s pipes.

It was played throughout the Greek and Roman world, particularly during races and games.

Given its place of importance and fabled past in great churches, it might surprise people to learn that the organ did not enter houses of worship until rather late in recorded history. In fact, as the Catholic Encyclopedia notes, objections to the organ’s use in churches continued until the 12th century.

The world’s oldest functioning and playable organ is in the Basilica of Valère in Sion, Switzerland. This astonishing instrument dates from about 1435. It would have been brought to Valère at the expense of Guillaume de Rarogne, a powerful figure who ended up as the Bishop of Sion. It still has most of its original case and a few pipes. The rest have been replaced or altered in restorations, the most recent in 1954.

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Handel composed a work of six organ concertos for chamber organ and orchestra from 1735-1736 – these organ concertos were the first of their kind and influenced many future composers. They also inspired Handel to write several more, including the Organ Concerto Op. 7 No. 1 in B flat major which is much grander and more majestic than the earlier concertos and unique within the series in that it had an independent pedal part.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1785-1750)

Bach’s ‘Little Fugue’ is one of the composer’s best-known and most recognizable melodies. This piece simply bursts with enjoyment and we get to savor the first theme for a relatively long time. It is also a reasonably easy and fun piece to play, despite it sounding more complex.

5th Symphony in F – Mvmt V – Toccata

Charles-Marie Widor (1844-1937)

The son and grandson of organ builders, Widor began his studies under his father and at the age of 11 became organist at the secondary school of Lyon. As a composer Widor is best remembered for his 10 symphonies for organ. Individual movements from many of his organ symphonies have become standard elements in recital repertory, most notably the “Toccata” from the Fifth.

Land of Hope and Glory, Pomp and Circumstance Military March No. 1

Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

Known in the USA as the “Graduation March” as it’s the most common processional tune at high school and graduation ceremonies, Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 is also well known for its reception two days after it first premiered in 1901 – it is the only piece in history of the London Promenade Concert in the Queen’s Hall, London, to be played for a second encore. Since then, it has grown further in popularity and is one of Elgar’s most famous works.

Leon Boellmann (1862-97)

Although he managed to amass a catalog of more than 150 compositions before his untimely death, Boëllmann’s best known work by far is the four-movement Suite Gothique. The title highlights the work’s retrospective musical characteristics but also describes the aura of grandeur evoked by the first, second, and fourth movements. The first is essentially a study in echo effects. This is followed by a grand minuet and then an introspective prayer to the Virgin Mary. The final toccata, with its menacing pedal theme and perpetual motion accompaniment, has long been a staple of concert programs.

William Walton (1902-83)

Premiered at the coronation of King George VI in 1937, unsurprisingly this grand piece has stood the test of time as Walton’s most popular composition. It has since been performed at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 as well as the recessional piece to the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton in 2011.

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921)

This is indeed a remarkable symphony – one of the most technically advanced and sophisticated of the late 19th century, packed with innovations for the time, and without doubt the pinnacle of Saint-Saens achievements.

He does away with the old structures and produces a work of two halves although you could say, with each half split in two, there is a nod to the old four movement convention.

He introduces the piano as well as the organ into his symphony producing an ingenious work for four hands alongside the orchestra.

The organ’s introduction is especially subtle, and beautifully crafted, whilst the theme itself – based on the old Latin plainchant Dies Irae – is revealed in both major and minor keys throughout the symphony until fully and thrillingly performed by the organist in the closing finale. This recurring theme, transformed over the course of the symphony was an idea first developed by Liszt, so the dedication by Saint-Saens to his friend is both personally touching and musically appropriate.

Saint-Saens was known to champion form above expression in his music, and heavily criticized others who thought differently, but if there was ever an example of how the two could combine to stunning and brilliant effect, it is this final symphony from Saint-Saens at his most expressive and inventive.

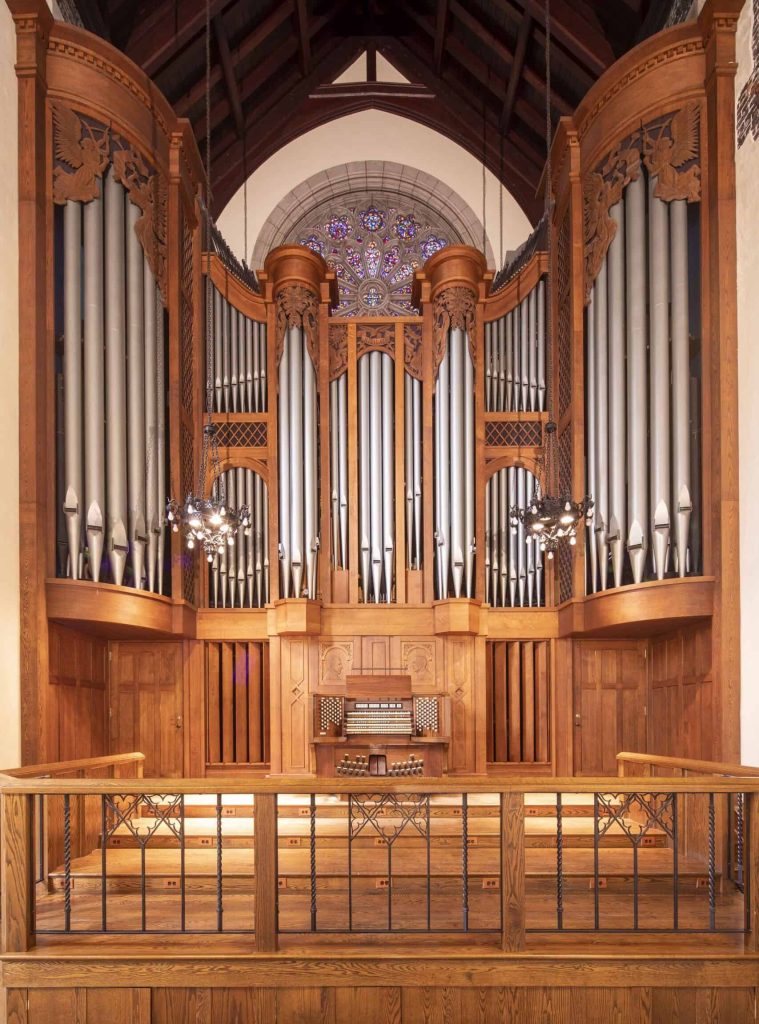

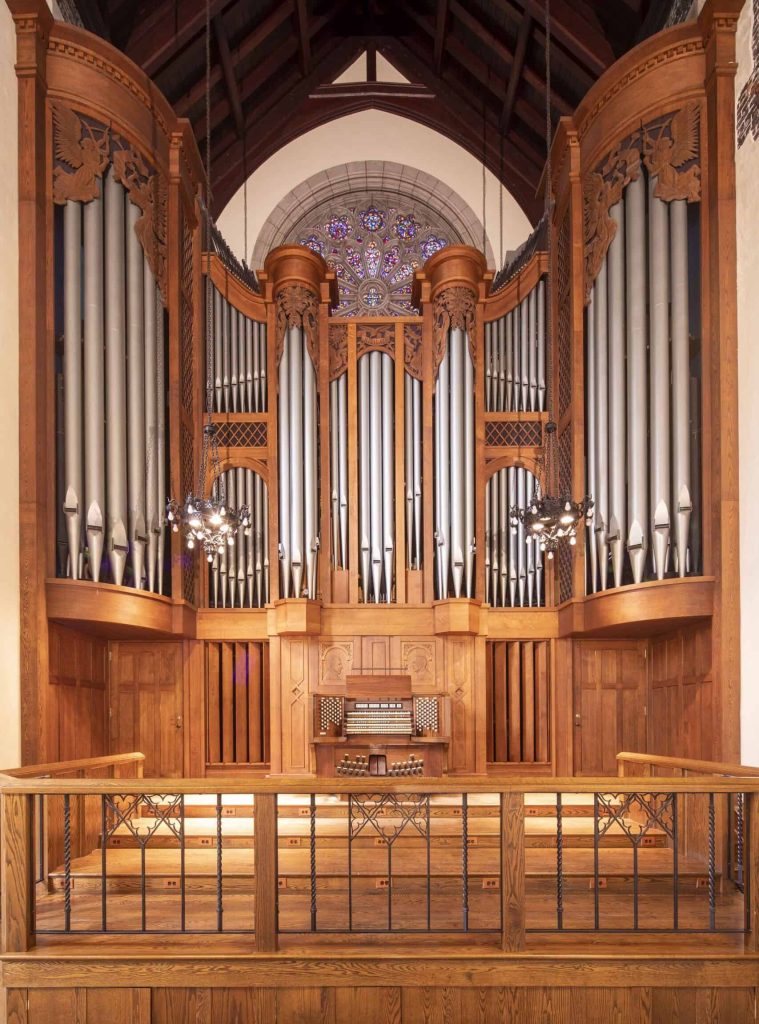

The pipe organ is a musical keyboard instrument that creates sound by pushing air under pressure through pipes which correspond to a particular keyboard. Pipe organs have a variety of pipe ranks of different tone, pitch, and volume that can be used on their own or in combination.

For an instrument to qualify as a pipe organ, it should have at least one manual (keyboard) and one rank of pipes. In larger instruments it can have as many as seven manuals and hundreds of pipe ranks.

A well built pipe organ is an exceptionally durable instrument, unlike the electronic and digital versions. With biannual tuning, regular maintenance and re-leathering every 50 years, it could last for centuries.

The organ was invented in ancient Egypt. This first organ is credited to Ctesibius, a mechanic who lived in Alexandria in the third century, B.C., who used water to make music through the organ’s pipes.

The organ was invented in ancient Egypt. This first organ is credited to Ctesibius, a mechanic who lived in Alexandria in the third century, B.C., who used water to make music through the organ’s pipes.

It was played throughout the Greek and Roman world, particularly during races and games.

Given its place of importance and fabled past in great churches, it might surprise people to learn that the organ did not enter houses of worship until rather late in recorded history. In fact, as the Catholic Encyclopedia notes, objections to the organ’s use in churches continued until the 12th century.

The world’s oldest functioning and playable organ is in the Basilica of Valère in Sion, Switzerland. This astonishing instrument dates from about 1435. It would have been brought to Valère at the expense of Guillaume de Rarogne, a powerful figure who ended up as the Bishop of Sion. It still has most of its original case and a few pipes. The rest have been replaced or altered in restorations, the most recent in 1954.

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Handel composed a work of six organ concertos for chamber organ and orchestra from 1735-1736 – these organ concertos were the first of their kind and influenced many future composers. They also inspired Handel to write several more, including the Organ Concerto Op. 7 No. 1 in B flat major which is much grander and more majestic than the earlier concertos and unique within the series in that it had an independent pedal part.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1785-1750)

Bach’s ‘Little Fugue’ is one of the composer’s best-known and most recognizable melodies. This piece simply bursts with enjoyment and we get to savor the first theme for a relatively long time. It is also a reasonably easy and fun piece to play, despite it sounding more complex.

5th Symphony in F – Mvmt V – Toccata

Charles-Marie Widor (1844-1937)

The son and grandson of organ builders, Widor began his studies under his father and at the age of 11 became organist at the secondary school of Lyon. As a composer Widor is best remembered for his 10 symphonies for organ. Individual movements from many of his organ symphonies have become standard elements in recital repertory, most notably the “Toccata” from the Fifth.

Land of Hope and Glory, Pomp and Circumstance Military March No. 1

Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

Known in the USA as the “Graduation March” as it’s the most common processional tune at high school and graduation ceremonies, Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 is also well known for its reception two days after it first premiered in 1901 – it is the only piece in history of the London Promenade Concert in the Queen’s Hall, London, to be played for a second encore. Since then, it has grown further in popularity and is one of Elgar’s most famous works.

Leon Boellmann (1862-97)

Although he managed to amass a catalog of more than 150 compositions before his untimely death, Boëllmann’s best known work by far is the four-movement Suite Gothique. The title highlights the work’s retrospective musical characteristics but also describes the aura of grandeur evoked by the first, second, and fourth movements. The first is essentially a study in echo effects. This is followed by a grand minuet and then an introspective prayer to the Virgin Mary. The final toccata, with its menacing pedal theme and perpetual motion accompaniment, has long been a staple of concert programs.

William Walton (1902-83)

Premiered at the coronation of King George VI in 1937, unsurprisingly this grand piece has stood the test of time as Walton’s most popular composition. It has since been performed at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 as well as the recessional piece to the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton in 2011.

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921)

This is indeed a remarkable symphony – one of the most technically advanced and sophisticated of the late 19th century, packed with innovations for the time, and without doubt the pinnacle of Saint-Saens achievements.

He does away with the old structures and produces a work of two halves although you could say, with each half split in two, there is a nod to the old four movement convention.

He introduces the piano as well as the organ into his symphony producing an ingenious work for four hands alongside the orchestra.

The organ’s introduction is especially subtle, and beautifully crafted, whilst the theme itself – based on the old Latin plainchant Dies Irae – is revealed in both major and minor keys throughout the symphony until fully and thrillingly performed by the organist in the closing finale. This recurring theme, transformed over the course of the symphony was an idea first developed by Liszt, so the dedication by Saint-Saens to his friend is both personally touching and musically appropriate.

Saint-Saens was known to champion form above expression in his music, and heavily criticized others who thought differently, but if there was ever an example of how the two could combine to stunning and brilliant effect, it is this final symphony from Saint-Saens at his most expressive and inventive.