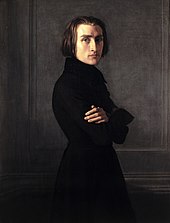

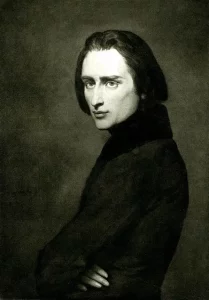

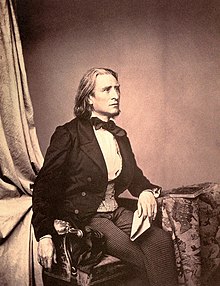

The greatest piano virtuoso of the Romantic era (and arguably of all time), Liszt’s astounding talent expanded the scope of what a piano could do, transforming the instrument into an expressive powerhouse that approached the range and complexity of a full symphony orchestra. Liszt’s mind-blowing piano prowess, coupled with a dynamic and charismatic performance style, made his concerts must-see events and garnered him “rock star” status the likes of which the world had never seen before.

The greatest piano virtuoso of the Romantic era (and arguably of all time), Liszt’s astounding talent expanded the scope of what a piano could do, transforming the instrument into an expressive powerhouse that approached the range and complexity of a full symphony orchestra. Liszt’s mind-blowing piano prowess, coupled with a dynamic and charismatic performance style, made his concerts must-see events and garnered him “rock star” status the likes of which the world had never seen before.

While Liszt’s name will forever be synonymous with dazzling piano pyrotechnics, stopping here vastly under-represents the depth of his contributions to music. In addition to expanding the piano’s scope, Liszt’s compositions were often defined by a forward-looking sense of harmonic adventure, and his later works evolved away from flashy showpieces and towards a leaner style that pushed tonal boundaries and anticipated the 20th century musical language to come.

Liszt’s interest in music began with his father, who was a musician and personally knew classical giants such as Haydn and Beethoven. Adam Liszt, his father, worked at Esterhazy, the same estate where Haydn worked for much of his life. Young Liszt would listen to his dad play piano, and began lessons and composition with him as a young boy.

In 1833, Liszt began a relationship with the Countess Marie d’Agoult. In 1835, she left her husband (it had been a marriage of convenience) and joined Liszt in Geneva. D’Agoult had three children with Liszt; however, she and Liszt did not marry (she never divorced the count), maintaining their independent views and other differences while Liszt was busy composing and touring throughout Europe.

In 1833, Liszt began a relationship with the Countess Marie d’Agoult. In 1835, she left her husband (it had been a marriage of convenience) and joined Liszt in Geneva. D’Agoult had three children with Liszt; however, she and Liszt did not marry (she never divorced the count), maintaining their independent views and other differences while Liszt was busy composing and touring throughout Europe.

In 1836, Liszt found himself with a child to support and very little money. He knew he had an incredible piano talent and decided to begin performing. He spent almost a decade touring Europe and performing relentlessly, usually 3-4 times a week (that’s more than a 1000 concerts).

Franz Liszt was a showman. He loved spectacle and used it to keep his audience hooked. During his tours, Liszt pioneered the solo recital, even coining the term. Most of the conventions of the modern recital exist because of Liszt.

Liszt was a showman. He loved spectacle and used it to keep his audience hooked. During his tours, Liszt pioneered the solo recital, even coining the term. Most of the conventions of the modern recital exist because of Liszt.

* He was the first to play music from a range of periods (from Bach to Chopin).

* He lifted the piano lid to reverberate its sound through the hall and played entirely from memory.

* Unusually, his tours were also unaccompanied. Without even a page-turner, Liszt could completely occupy the full attention of the crowd.

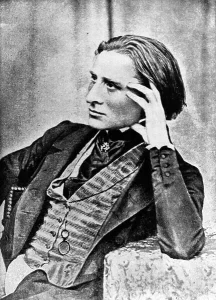

* He was also a fan of flamboyance. On stage, he would throw his white gloves to the ground before playing. He was never without his Hungarian sword and made a point of tossing around his signature shoulder-length hair during performances. Naturally, his pianos were turned sideways to show off his handsome profile to the crowd.

* His repertoire also served this spectacle. Liszt spruced up works by Beethoven or Weber with extra runs, cadenzas, and presto tempi.

In short, Franz Liszt could command a stage. He had star quality and knew it. His concerts were deliberately theatrical and made Liszt a larger-than-life celebrity.

Hungarian Rhapsody No. 6 in D-Flat Major, S. 244 – 1847

The Hungarian Rhapsodies are a set of 19 piano pieces based on Hungarian folk themes and noted for their difficulty. Liszt also arranged versions for orchestra, piano duet, and piano trio. He incorporated many themes he heard in his native western Hungary, which he believed to be folk music though many were, in fact, tunes written by members of the Hungarian upper middle class often played by Roma (Gypsy) bands. Liszt incorporated a number of effects unique to the sound of Gypsy bands into the piano pieces including the twanging of the cimbalom and syncopated rhythms.

Quite rightly, Franz Liszt has been called the world’s first rock star. Wherever he went he inspired delirium in starstruck fans. Women reportedly fought over handkerchiefs Liszt had used, or crafted his broken piano strings into bracelets. They pasted his likeness onto their brooches and cameos. Packed crowds stole cuttings of his hair, his coffee dregs — even his cigar butts. Concert halls were pandemonium.

Quite rightly, Franz Liszt has been called the world’s first rock star. Wherever he went he inspired delirium in starstruck fans. Women reportedly fought over handkerchiefs Liszt had used, or crafted his broken piano strings into bracelets. They pasted his likeness onto their brooches and cameos. Packed crowds stole cuttings of his hair, his coffee dregs — even his cigar butts. Concert halls were pandemonium.

Articulating the craze in 1844, Heinrich Hein penned the term “Lisztomania.” He described it as a contagion in medical terms: “And what is the real cause of this phenomenon? A physician whose speciality is the disorders of women and with whom I conversed as to the magic which our Liszt exercises on his public, smiled mysteriously and told many things of magnetism, galvanism, electricity, of contagion in an overheated hall.”

Totentanz, S. 525 (1849)

Horrific scenes during the Paris cholera epidemic of 1832 inspired Liszt to use the Gregorian plainchant melody Dies Irae in a number of works, most notably in Totentanz (Dance Of Death) for piano and orchestra. Since it is based on Gregorian material, Liszt’s Totentanz contains Medieval-sounding passages with canonic counterpoint, but the most innovative aspect of the arrangement is the extremely modern and percussive piano part.

Liszt’s longest-running relationship (40 years) was with Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein. They never married, though they wanted to – husband refused to divorce her and took her estate, leaving her with little. The two had children together, and she was the one to convince Liszt to focus on composing after his epic decade of touring. Because of this, he never became “washed up”. By finishing all the touring at age 35, he quit at the peak of his game.

Liszt’s longest-running relationship (40 years) was with Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein. They never married, though they wanted to – husband refused to divorce her and took her estate, leaving her with little. The two had children together, and she was the one to convince Liszt to focus on composing after his epic decade of touring. Because of this, he never became “washed up”. By finishing all the touring at age 35, he quit at the peak of his game.

Liebesträum No. 3 (1850)

The Liebesträume are a set of three solo piano pieces published in 1850. This is the third and most popular of the set. Liszt’s inspiration is poetry and each of the pieces represents love in a different form. In this final piece of the set, love is considered to be unconditional and in its highest form. Liszt chooses the warm key of A flat major and a single melodic idea that threads its way throughout the work. Broadly speaking the form is in three sections although the piece is continuous. Each of these smaller parts is pillared by a mighty cadenza-like passage where Liszt cannot help but display his musical prowess. The piece is an abundant expression of joy and elation and it is not hard to see why it has become one of Liszt most enduring works.

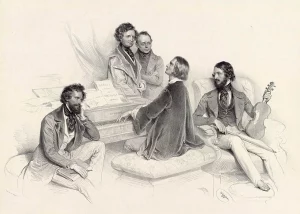

The “Almost” Duel – Alcohol, cigars and cognac were but three of Liszt’s worldly vices, and when it was time to party he sometimes had no reservations about going extra hard. In 1846, Liszt attended a banquet in Prague, and was asked to give a speech. Composer Hector Berlioz, who was also in attendance, remembered what that was like: “Unhappily, if he spoke well, he drank likewise. The fatal cup set such tides of champagne flowing that all Liszt’s eloquence was shipwrecked in it.” Needless to say, the piano man needed some help getting home. At 2 o’clock in the morning, Berlioz and his secretary did the classic “hoist our buddy between us and drag his feet move” in an effort to get Liszt back to his hotel. On the way, they encountered another rowdy partygoer. They exchanged words, and Berlioz had to work extra hard to talk Liszt out of dueling right there on the street.

The best part? Liszt was scheduled to give a concert the following day, and thirty minutes before concert time he was still asleep. The hotel staff woke him up, rushed him into a carriage and delivered him to the concert hall right on time. Berlioz remembered Liszt played “as I do not think he has ever played before in his life. Verily, there is a God — for pianists.”

La Campanella (1851)

One of the most technically challenging piano pieces ever written, La Campanella (“little bell”) is based on a melody by the king of virtuoso violinists, Niccolò Paganini.

Liszt was known for being generous to friends and family (as well as people he didn’t know, which we’ll talk about in a moment). He often let people stay at his place, including piano students who didn’t have anywhere to go, and various friends such as Hector Berlioz when he was poor. In addition to an ever-rotating ensemble of guests, Liszt’s Weimar household also included a family cat named Madame Esmeralda, and a loud guard dog named Rappo.

Liszt was known for being generous to friends and family (as well as people he didn’t know, which we’ll talk about in a moment). He often let people stay at his place, including piano students who didn’t have anywhere to go, and various friends such as Hector Berlioz when he was poor. In addition to an ever-rotating ensemble of guests, Liszt’s Weimar household also included a family cat named Madame Esmeralda, and a loud guard dog named Rappo.

Liszt’s Transcription of Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique – Le Bal

Liszt’s piano transcriptions are less-known nowadays, but they were a big deal when he was alive. By making transcriptions of other composers’ works, he was able to popularize them and drive interest toward composers he deemed worthy. One example is Hector Berlioz. By penning Symphony Fantastique for piano solo and performing it frequently, he helped Berlioz out of destitution and obscurity. Another composer he helped in this way was Richard Wagner, who had been exiled. The two ended up becoming very close.

Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 in C-sharp Minor (1851)

The Hungarian Rhapsodies Nos 1-6 are among Liszt’s most extroverted and popular orchestral works. Hungarian Rhapsody No 2 in C sharp minor is by far the most famous of the set. In both the original piano solo and orchestral arrangements, the composition has enjoyed widespread use in cartoons, and its themes have also served as the basis of several popular songs. This orchestral version is unusual in that includes traditional Gypsy instruments, rather than just the standard orchestral instruments.

And now for another tales of Liszt’s generosity. A young woman just starting out as a piano teacher billed herself as a student of Liszt. To her horror, she learned the Liszt was going to perform in her city. As soon as he arrived, she threw herself at his feet, confessing the lie. He sat her down at the piano and asked her to play, made a few suggestions for improvement, and sent her on her way, telling her that she was now, indeed, a student of Liszt.

Piano Sonata in B Minor (1854)

This sonata was composed by Liszt during the year 1854 and is dedicated to Robert Schumann. It as a work that has a duration of around thirty minutes during which the gifts of even the ablest pianist are stretched. What is important to recognize is that the whole sonata is really a single movement form based on a single motif.

Les Preludes, S. 97 (1854)

Les Preludes is perhaps the most well-known of Liszt’s symphonic poems, a genre of music which Liszt created. The symphonic poem is basically orchestral music (no vocals) based on art/literature that tells a story through music. Les Preludes is based on a poem by Alphonse de Lamartine which included the poetic text: “What else is life but a series of preludes to that unknown song, the first and solemn note of which is sounded by Death?”

A Faust Symphony, S. 108 (1857)

A Faust Symphony In Three Character Pictures was inspired by Goethe’s drama Faust. Liszt does not attempt to tell the story of Faust but creates musical portraits of the three main characters. He developed his musical technique of thematic transformation, in which a musical idea is developed by undergoing various changes. Hector Berlioz had just composed La Damnation De Faust, which he dedicated to Liszt. Liszt returned the favor by dedicating his symphony to Berlioz.

When Liszt was a young man, he fell in love with one of his students, but her father forbade the relationship. This period of heartsickness inspired him to become a priest (an ambition he carried throughout his life), but his mother talked him out of it. In the 1860s, Liszt lost two of his children – his 20-year old son Daniel, and 26-year old daughter Blandine, leaving just one living daughter, Cosima. After these tragedies, he retreated to a monastery and received the four minor orders, which meant he could be called Abbé Liszt.

When Liszt was a young man, he fell in love with one of his students, but her father forbade the relationship. This period of heartsickness inspired him to become a priest (an ambition he carried throughout his life), but his mother talked him out of it. In the 1860s, Liszt lost two of his children – his 20-year old son Daniel, and 26-year old daughter Blandine, leaving just one living daughter, Cosima. After these tragedies, he retreated to a monastery and received the four minor orders, which meant he could be called Abbé Liszt.

In July 2, 1881 Liszt had a terrible accident at a Hotel in Weimar. He fell down the hotel stairs and was not able to walk for eight weeks. He never recovered fully from the accident which affected him up to the point of death. In July 31, 1886 Liszt died from pneumonia and was buried on August 3, 1886 in Bayreuth, Germany.

In July 2, 1881 Liszt had a terrible accident at a Hotel in Weimar. He fell down the hotel stairs and was not able to walk for eight weeks. He never recovered fully from the accident which affected him up to the point of death. In July 31, 1886 Liszt died from pneumonia and was buried on August 3, 1886 in Bayreuth, Germany.