Wagner was the most influential musician of the era following Beethoven. His new use of harmony and his explicit attention to the sensuous nature of the musical experience broke away from older and more formal types of musical construction. To this day, the unresolved dissonance of the so-called “Tristan chord” at the beginning of Tristan und Isolde is often seen as the start of musical modernism.

Wagner was the most influential musician of the era following Beethoven. His new use of harmony and his explicit attention to the sensuous nature of the musical experience broke away from older and more formal types of musical construction. To this day, the unresolved dissonance of the so-called “Tristan chord” at the beginning of Tristan und Isolde is often seen as the start of musical modernism.

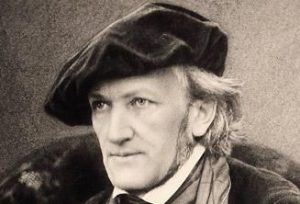

Richard Wagner’s radical works sent shock waves across nineteenth century Europe. Each of his mature operas expresses deep insights into the nature of the human condition, influencing fields as diverse as philosophy, politics and psychiatry. They have also spurred emulation and reaction among musicians, writers and many other artists. A charismatic and often capricious figure, Wagner was – and remains – one of the most controversial and influential composers in musical history.

One of Wagner’s innovations was to employ leitmotifs, brief musical themes associated with specific characters, objects or ideas, which are subtly woven into the greater musical fabric. This technique, influenced by Berlioz’s “fixed idea” invention, was the direct ancestor of some of the melodies by future composers such as Richard Strauss — not to mention the ancestor of the themes of Darth Vader, Luke Skywalker, Princess Leia, and Obi-Wan Kenobi.

Through mythological settings he was able to create powerful allegories exploring issues with universal resonance, such as love, power, heroism and duty. Each of his operas contains orchestral passages – whether overtures, preludes, or other excerpts – that have found a place in the concert hall repertoire. Hearing them outside their operatic context reveals just how powerful Wagner’s musical gift was. His music has the ability to sweep the listener along in an endless stream of expressively orchestrated sound.

Born in Leipzig in 1813, Wilhelm Richard Wagner was convinced early on of his own genius, despite a music teacher once supposedly saying he used to “torture the piano in a most abominable fashion.” Wagner wrote his first dramas as a schoolchild, and he would go on to write the libretti (the texts for an opera) for his operas himself, which was highly unusual at the time. To him, text and music always went together, with music serving the drama.

The young Wagner secured short-term jobs in several German towns, during which he wrote his earliest operas (rarely performed even today) and married his first wife, Minna Planer. He spent the next decade composing his major mature works, as well as writing extensively. He also had a number of affairs. Performances of his operas were rare, his marriage broke up and his debts increased.

The opera Rienzi was deliberate built on such a stupendous scale that it could only be offered to some royal theater. Wagner had read Bulwer Lytton’s Rienzi, The Last of the Barons, and “was carried away by this picture of great political and historical event.” Wagner wrote as follows in explanation of the beginning of the work: “Grand opera, with its scenic and musical display, its sensationalism and massive effects, loomed large before my eyes: the aim of my artistic ambition was not merely to imitate it, but with reckless extravagance, to outdo it in every particular.” He carried out his intentions so well that the premiere performance at Dresden in 1842 lasted six hours.

Tannhäuser is Wagner’s retelling of a medieval German legend of temptation and redemption. A minstrel-knight, Tannhäuser, is seduced by Venus and is a virtual prisoner in her grotto in the Venusberg. He finally calls upon the Virgin Mary and escapes Venus, only to set off on a long and bitter quest seeking pardon for his sins.

Lohengrin (1848) – Prelude and Bridal Chorus

Lohengrin (1848) – Prelude and Bridal Chorus

Lohengrin is a romantic opera in three acts first performed in 1850. The story of the eponymous character is taken from medieval German romance, notably the Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach. The opera has proved inspirational towards other works of art. Among those deeply moved by the fairy-tale opera was the young King Ludwig II of Bavaria. ‘Der Märchenkönig’ (‘The Fairy-tale King’) as he was dubbed later built his ideal fairy-tale castle and dubbed it “New Swan Stone,” or “Neuschwanstein”, after the Swan Knight. The most popular and recognizable part of the opera is the Bridal Chorus. The first production of Lohengrin was in Weimar, Germany in 1850 under the direction of Franz Liszt, a friend and early supporter of Wagner.

Wagner was constantly on the run, often in an attempt to flee his creditors. He frequently took off to foreign countries. One such flight saw him and his wife flee for London by sea. Another anecdote says he gave Viennese tax investigators the slip by dressing as a woman.

Wagner was constantly on the run, often in an attempt to flee his creditors. He frequently took off to foreign countries. One such flight saw him and his wife flee for London by sea. Another anecdote says he gave Viennese tax investigators the slip by dressing as a woman.

His political activities also got him into hot water. In 1848, while in the eastern German state of Saxony, he joined the revolutions against the political order that were unfolding across Germany. Accused of treason, he sought refuge in Zurich, Switzerland, for many years until he was pardoned by the emperor.

Das Rheingold (1854) – Prelude

The ‘Prologue’ to Wagner’s four opera cycle The Ring of the Nibelung revolves around a gold ring, which gives unlimited power to the wearer who renounces love, and by the end of the opera has already changed hands three times. It introduces the characters that will drive this drama to its epic conclusion, and the musical themes that Wagner develops through the cycle.

Antisemitism was widespread in mid-19th century Europe. In 1850, Wagner published an antisemitic pamphlet entitled Judaism in Music. In it, he notoriously denied Jews creative abilities, implied that they were foreign to the cultures they lived in and also wrote that they posed a threat to national identity. Wagner also voiced his support for the idea that Jews should abandon their Judaism or be eradicated. Nevertheless, he maintained contact with prominent Germans of Jewish heritage and was not averse to Jewish fans and donors financially supporting his Bayreuth Festival.

Decades later, the Nazis appropriated Wagner as a composer. Adolf Hitler cherished his music and also esteemed him as an early herald of anti-Semitism in Germany. For the racist and nationalist opponents of German modernism, Wagner was, even during the composer’s lifetime, an important figure.

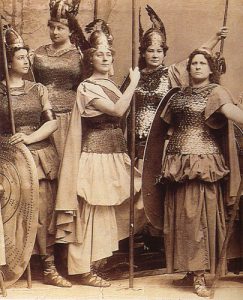

Die Walküre (1856), WWV 86b, Act 3: Ride of the Valkyries

Die Walküre (1856), WWV 86b, Act 3: Ride of the Valkyries

Die Walküre (The Valkyrie) is the second of the four epic operas in Wagner’s Der Ring Des Nibelungen (usually known simply as The Ring Cycle). The Valkyries of the title are an army of maidens who ride through the air on horseback, led by Brünnhilde, Wotan’s warrior-daughter, who ends the opera surrounded by a circle of flames. The best known media use of Die Walküre is in the 1979 film Apocalypse Now when the music is played as the American helicopters bombard a Vietnamese village.

Siegfried (1857) – Act III Prelude

Third part of Wagner’s massive operatic tetralogy centers upon Siegfried who slays the evil Fafnor (disguised as a dragon), and the wretched dwarf Mime, before rescuing Brünnhilde from the ring of fire. Think of it as a sort of nineteenth-century version of The Lord Of The Rings trilogy, albeit with a fourth instalment.

Tristan and Isolde (1859) – Prelude and Liebstod

Tristan and Isolde (1859) – Prelude and Liebstod

Tristan und Isolde marked a bold advance in Wagner’s work, and its musical-dramatic style was quite different from anything that had come before. Wagner had been developing the use of leitmotifs in his earlier operas. Here, they blossom into a generalized interweaving of motifs which, though they transmit particular flavors, are for the most part indistinctly linked to individual characters or concepts.

But, above all, it is for its harmony that Tristan und Isolde is universally considered a watershed work. In the opening measures of the Prelude—in fact, in its very first chord, preceded only by unharmonized notes of melody—we hear a curious chord, neither consonant nor strikingly dissonant, that will lend an uncanny sense of ambivalence and yearning throughout the opera’s whole immense span. Wagner’s writing is highly chromatic in this work, testing the limits of traditional tonality through unresolved suspensions and other imaginatively deployed dissonances.

In 1864, Wagner’s life turned two corners. The new king of Bavaria, Ludwig II, paid off the composer’s debts and commissioned performances of new operas, including Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. That same year, Wagner moved in with Cosima von Bülow, the already married daughter of the composer Franz Liszt, and began a family. Wagner demanded that Liszt support his new family and Liszt, having become a major admirer of Wagner’s work, agreed.

In 1864, Wagner’s life turned two corners. The new king of Bavaria, Ludwig II, paid off the composer’s debts and commissioned performances of new operas, including Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. That same year, Wagner moved in with Cosima von Bülow, the already married daughter of the composer Franz Liszt, and began a family. Wagner demanded that Liszt support his new family and Liszt, having become a major admirer of Wagner’s work, agreed.

Siegfried Idyll is a symphonic poem for chamber orchestra reflecting a gentle, tender side of the composer. Wagner composed the Siegfried Idyll as a birthday present for his second wife, Cosima, and it was first performed by a small ensemble, on a staircase in their villa, on Christmas Day 1870. Wagner originally intended the Siegfried Idyll to remain a private piece but, due to financial pressures, he decided to sell the score to publisher B. Schott in 1878.

Reproduction of the set design by Max Bruckner of the final scene from Gotterdammerun, showing Valhalla on fire.

Götterdämmerung (1874) – Siegfried’s Death and Funeral March

Götterdämmerung (The Twilight Of The Gods) is the fourth and final work of Wagner’s opera cycle Der Ring Des Nibelungen. A series of dramatic deceptions leads to the murder of Siegfried, Brünnhilde’s suicide, the destruction of a world order and the return of the Ring to the Rhinemaidens. By the opera’s end world order has been restored – but at a devastating cost.

Richard Wagner, Franz Liszt, Cosima Wagner and Hans von Wolzogen, 1881

Wagner worked on his Ring Cycle for many years and by 1871 he had chosen the Bavarian town of Bayreuth as the festival location where the entire work was to be performed for the first time. The family moved and in 1876 the Ring received its first performance in the specially built theatre — all 15 hours of it. The festival was an artistic sensation and a financial disaster for Wagner personally, from which King Ludwig again rescued him.

His health failing, Wagner now concentrated on completing his final opera Parsifal, which opened at Bayreuth in 1882. Wagner died in Venice the following February.

Margravial Opera House in Bayreuth

Parsifal (1882) – Prelude

Wagner’s swansong, a masterpiece of sustained drama, is principally concerned with the retrieval by the Knights of the Holy Grail of the spear that pierced Christ’s side at his crucifixion. Wagner’s opening Prelude is an extraordinary expression in many respects. That it is called a Prelude, rather than an Overture (as is the operatic norm), is a particularly Wagnerian contrivance. Largely composed from the opera’s thematic motifs, it functions mainly as a preparation for the grandiose scope and tenor of the story that will unfold. With Wagner’s incomparable gifts at orchestrating and molding themes and harmonies, one is left somewhere between pious reflection and immeasurably deep awe.

This reverent reflection is precisely the frame of mind which Wagner intended for his listeners, as Parsifal was to be his ultimate achievement in art and social/religious theory. His artistic attempt to combine all of the arts (literature, music, graphic art) and religion into the “true art,” or opera as the sublime expression, certainly manifests itself in Parsifal. That he spent nearly a quarter of his life planning, financing, and building an opera house (the “Festspielhaus” in Bayreuth, Germany) dedicated solely to the production of his operas is only half of the megalomania of Richard Wagner. The Festspielhaus was intended to be a Shrine to Art and Purity, and those who took the pilgrimage to this sacred place far from the maddening crowds were to be purified by the sacrament of Wagner’s creations. Near the completion of the Festspielhaus he began writing a newspaper, the Bayreuther Blätter, devoted to expounding on his music and his social theories of racial purification. Obsessed as he was with his Christ complex, Parsifal was a fitting theme for consecrating his holy shrine with his “true art.” Wagner called it, not an opera, but a “Buhnenweihfestspiel” (meaning roughly stage-consecrating festival play), insisting that it could be produced only in Bayreuth for the term of its copyright.

In a century of revolution, Wagner was himself a revolutionary of a special kind. Intoxicated by his ideal of ancient Greece, he placed music and theatre at the center of an aspiration to remake the world with a focus on art and beauty. In his world view, the artist was the prophet and embodiment of the future. In his music this mythic vision reaches its climax at the close of the Ring cycle.

In today’s terms it can be said that Wagner’s nationalism moved from the revolutionary left to the nativist right. His belief in the possibility of enlightenment through German art is part of the explanation for his antisemitism. Towards the end of Wagner’s life, antisemitism became central to the whole culture of Bayreuth, and became even more virulent in the early 20th century.